Mind Matters is a newsletter written by Oshan Jarow, exploring post-neoliberal economic possibilities, contemplative philosophy, consciousness, & some bountiful absurdities of being alive. If you’re reading this but aren’t subscribed, you can join here:

Hello fellow humans,

This newsletter begins with a slightly longer-form read than usual. You can read it on my website if you prefer.

Let’s get right to it -

Civilization, Capitalism, and Kindness

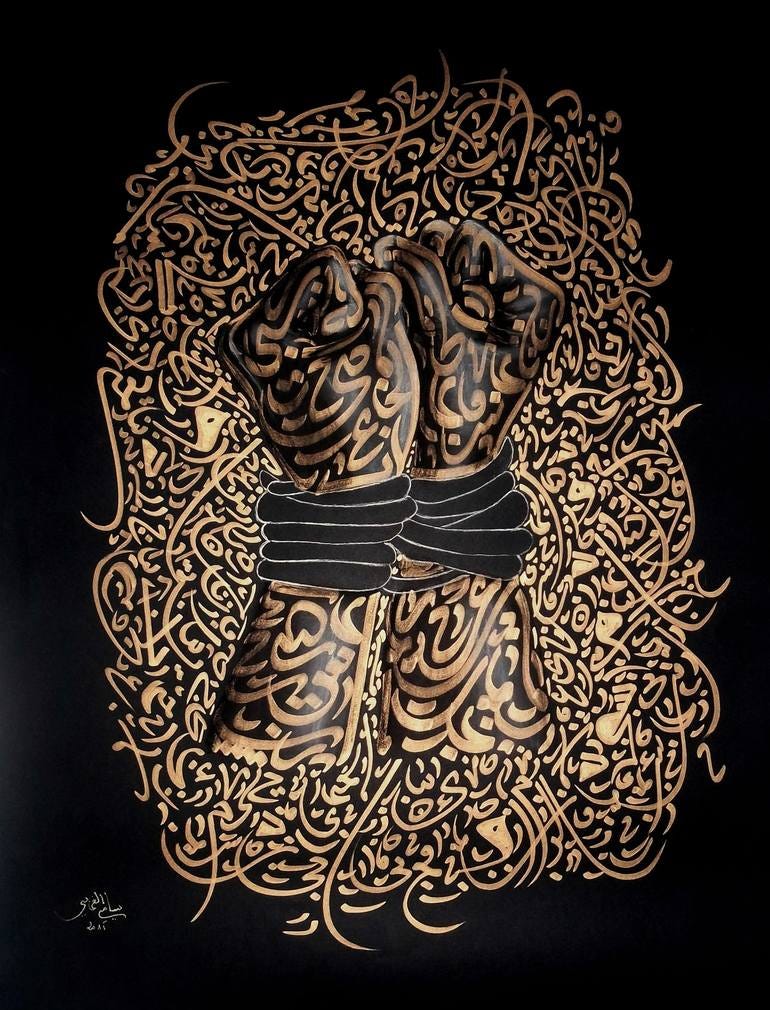

Art by Sami Gharbi

Freud believed that civilizational progress depended on the active repression of its citizens. In a deceptively humble footnote, he suggests that civilization - understood as the systematic process of repression for the purposes of progress - began the first time a male encountered fire and suppressed his urge to piss on it, which apparently prehistoric men enjoyed doing, allowing him to use the flame and reap the benefits of his managed repression. Presumably cooked fish, or something.

Freud's theory is a departure from the likes of Rousseau or Marx, both of whom took a more narrow view towards what exactly was responsible for repressing citizens: a capitalist society built upon the idea of private property.

What I find significant in either case, whether you follow Freud in thinking that repression is inherent to civilization, or Marx in thinking that repression is inherent to capitalist society, is their shared premise: to exist in society today is to be actively repressed by it.

Bickering over the source of repression is an important discourse. It determines whether the Marxist philosopher Herbert Marcuse's non-repressive society is possible. If the problem is capitalist society, hasten on to post-capitalism! But if it's civilization at large, short of an anarchistic dissolution of the state, the forecast remains repression (I can't say I'd be optimistic about the forecast of what'd come after an anarchistic dissolution of the state, either).

But we're too quick to follow the glimmer of a non-repressive society. We will not transcend capitalism, nor dissolve the state, by next week. So the immediate question we all face is how to live in the interim? We must all, as Lauren Berlant puts it in Cruel Optimism, "trade strategies for how best to live on, considering."

What does the present fact of repression mean for how we lead our lives? Would a careful consideration of this question suggest we do anything differently? I will suggest that we know the answer intuitively, but have yet to rationalize and grant it a place at the forefront of consciousness: the proper response to encountering a repressed, distorted being - which is all of us - is a default position of kindness.

…

Deviation, Distortion, the Othered Self

A repressive society creates distorted individuals. People who experience an incongruity between their socially produced selves and their interior sense of their own potentialities, their own being. We become othered from ourselves. The self who exists in relation to other people, to society, is not me. It is someone, or something else, if only slightly. Repressive societies produce a distorted kind of self. It's as if a magnetic force draws our paths of development from what we feel internally to be their natural course. We experience our own becoming as a deviation, and thus live with a growing tension, a chasm between our inmost sense of who we are, and the self that society reflects back to us. It's like Arthur Rimbaud's schism: I is another.

The experience of distortion, of developmental deviation, ranges from an imperceptible ripple in the basement of the psyche, to an unrelenting assault that finds us in every moment, like the rhythmic thrashing of tidal waves against a rocky shore. And it's in this state of distortion that we encounter our fellow citizens. To interact with another citizen is to encounter another distorted individual. And it is this fact, this shared basis of all social interaction, that positions kindness as the default stance from which we ought to encounter one another.

I suspect we know this intuitively. Consider an extreme example. Imagine, you're driving along a country road on a sunlit afternoon, and you notice a small figure up ahead on the road. You get closer, and make out a small animal dragging itself across the asphalt. An adult fox with burnt orange fur, apparently hit by traffic but still quite alive. Its two front legs are limp, smeared with blood. All it can do is push itself from behind using its functional hind legs, but each push inflicts pain as the front legs are scraped against the road. But fear propels it, it must go on, perhaps towards the nearby woods.

You might react to the fox in many ways. Perhaps you swerve around it, shaking your head and feeling sorry for it. You might stop your car and help it off the road. Or put it out of its misery with a nearby rock. However you react, there is an aching empathy, a painful desire to ease its suffering. We all share a common response: a starting point of kindness.

We know the proper response to a distressed, distorted being. One that is othered from itself, incapacitated from its full developmental potentiality. However you feel about the extremity of my metaphor that compares repressed citizens to maimed foxes, and whether you hold civilization or just capitalist society responsible, we are all encountering each other as variously distorted beings, who nevertheless drag ourselves along the asphalt. There is no one in society you will meet that isn't managing their own experience of distortion in one way or another, whether in their psyche's basement or the surfaces of their experience. There is no one you encounter for whom your starting position should not be one of aching empathy, of unconditional kindness [1].

[1] This exists as a formal idea in game theory: tit for tat. It states that you should begin every encounter with another player with a default orientation towards cooperation. From then on, you reciprocate their response. If they cooperate in turn, you follow. If they cross you, you cross them. But the optimal starting point is always cooperation.…

Non-Repressive Society

There are some quirks to framing kindness as conditional upon distortion. In Marcuse's non-repressive society, would kindness be obsolete? Would we then be free to encounter each other from any variety of starting points, so long as they are uninhibited by repression? Would the game theory of social interaction evolve?

I don't think so, but I won't take up that question here. More alluring is the question of non-repressive society's viability. Is it possible? What might it look like? Or, how might we get there? Marcuse:

"But Freud’s own theory provides reasons for rejecting his identification of civilization with repression. On the ground of his own theoretical achievements, the discussion of the problem must be reopened. Does the interrelation between freedom and repression, productivity and destruction, domination and progress, really constitute the principle of civilization? Or does this interrelation result only from a specific historical organization of human existence? In Freudian terms, is the conflict between pleasure principle and reality principle irreconcilable to such a degree that it necessitates the repressive transformation of man’s instinctual structure? Or does it allow the concept of a non-repressive civilization, based on a fundamentally different experience of being, a fundamentally different relation between man and nature, and fundamentally different existential relations?"

Who knows? But I suspect that we'll only find out if we operate from a basic relational stance of kindness in the interim. In other words, I suspect if there does exist a path towards non-repressive society, it begins only with kindness towards each and every distorted citizen of our repressed society.

I don’t mean this (only) in the ‘be kinder to the people you encounter in your life!’, Hallmark-y kind of way. I mean, especially, those people who you’ll never meet. I mean an institutional kindness that extends beyond that evolutionary preference we have for our kin. I mean designing economic policy to support people, rather than to get out of their way, as if swerving around that struggling fox and not looking back.

This leaves us with at least two possibilities. Either repression is inherent to civilization, and will thus persist so long as our civilization does (which, depending on your style, might not be such a distant prospect anymore). Therefore, there is no terminal point at which kindness is rendered obsolete, and our work is to figure out how to culture it. And how to live on, considering.

Or, if we achieve some form of a non-repressive society...then I have no idea what that'd mean, look like, or entail. But it'd be interesting to find out, so that seems like a positive outcome too.

[Thanks to Barnaby Raine, who planted the seed of this idea during his course on ‘Capitalism and the Self’.]

Quigley’s Recipe for Civilizational Evolution, or Decay

Reading Carroll Quigley’s The Evolution of Civilizations; the basic unit that drives civilizational evolution is what he calls an instrument of expansion.

An instrument of expansion is composed of three conditions:

The society must be organized in such a way that it has an incentive to invent new ways of doing things.

It must be organized in such a way that somewhere in the society there is accumulation of surplus - that is, some persons in the society control more wealth than they wish to consume immediately.

It must be organized in such a way that the surplus which is being accumulated is being used to pay for or to utilize new inventions.

In short, a civilizational instrument of expansion requires: an incentive to invent, an accumulation of surplus, and an application of that surplus to new inventions.

The notion of “surplus” keeps popping up. For Marx, surplus value (itself derived from surplus time) is the beating heart that drives the expansion of capitalism. For Martin Hägglund, reclaiming democratic ownership over our surplus time is at the heart of living truly free, spiritual lives.

The basic question - what is a society doing with its surplus? - lingers.

Also worth noting, Quigley’s point is that civilizations decline when their instruments of expansion harden into institutions.

An instrument arises to meet a particular social need, but over time, that instrument ossifies into an institution that takes on a life of its own, and functions more to perpetuate itself and serve its own needs than the original needs it arose to satisfy. This creates rigidity, conflict, and ultimately, decline.

Decaying institutions can be replaced by new instruments, but this requires an investment of both surplus wealth and time that allows for the research and development that drives innovation.

This all links really nicely with the sociologist Erik Olin Wright’s theory of change, where universal basic income frees up time, space, and wealth for broad social experimentation with new ways of living. UBI isn’t seen as the solution to anything, but it plays a role in distributing surplus so as to allow more citizens to engage in social innovation, which will hopefully yield new, fresh instruments of expansion that can replace our ossifying institutions.

This was the basic idea behind my Against Time Inequality essay. It imagined a range of 6 policies that can democratize time and wealth, not as a solution to anything, but as a spur for social innovation. A kind of holding pattern while we figure out how to revitalize our institutions, so that their decline doesn’t pull us down with them.

That’s All

As always, you can respond directly to this email with thoughts, comment on the Substack version of this post for public discussion, or reach out on Twitter. You can find more essays & podcasts on my website. I’m here for conversation & community.

If you have a friend who might dig this newsletter, or you want to support me, consider sharing it. The more people on this network, the more possibilities we can cook up, and the more time I can devote to these projects.

Until next time,

Oshan

As much as I appreciate your style of writing, I can't help but think the poetic flourish has somewhat obscured some underlying logical leaps. Is it really fair to characterize civilization, or capitalism more specifically, as "repressive"? What is the basis for this? Is repression a denial of being able to do what you want? Am I repressed for not being able to piss in a fire? Am I repressed for not being able to murder whomever I please? Am I repressed for being unable to pick up a stone too heavy for me? The physical world applies constraints to our agency. The social world applies them as well. These do not equate to repression. I think this assumption, and subsequently normatively-charged argument, needs to be revisited.