Mind Matters

Universal Basic Decommodification // Generative Identity

Hello hello,

Firstly, new podcast. I spoke with Gustav Peebles, economic anthropologist at The New School and author of one of the most fascinating essays on Adam Smith I’ve read. Here’s the episode page with links, topics, etc.

If, like me before encountering Gustav’s work, you’ve never heard of “splenetic philosophy”, I wrote about it in a previous newsletter.

Universal Basic Decommodification

For the past 3 months, though truly for the past 5 years, I’ve been working on a long-form essay. It’s an attempt to bring together my two worlds: economics, and consciousness.

I’ve always suspected economics and consciousness are intimately connected. They interweave, spiral, and braid together so tightly that they merge into one another. The economic arrangements that govern our lives and the ways in which we experience our own consciousness cannot be separated.

It pains me to summarize what it’s about, because to say anything is to leave so much unsaid. But if I had to cobble together a “thesis”, I’d share these two (non-consecutive) paragraphs from the introduction:

“Our everyday experience of what it’s like to exist, ‘ordinary consciousness’, is in fact a psychedelic state - the mind manifested from its set and setting: the tangled web of mental, physical, and social conditions whose threads are woven into the tapestry of consciousness. The psychedelic community has long studied the importance of set and setting on the trip experience. This essay explores the economic design of society as a set and setting that conditions the everyday trip of ordinary consciousness. I’ll explore how the current economic landscape functions as a set and setting that monopolizes the production of consciousness, subordinating the process of human development to the interests of capital.

…In particular, I’ll explore universal basic income (UBI) as one possible intervention in the hyper-capitalist distortion of human development. By securing decommodified time for all in the form of universal, unconditional income, UBI enables behaviors, relations, and projects - ways of living - that transcend the logic of capital. These diversities of behavior would enrich social complexity and introduce new possible directions for human development.”

When I say “the current economic landscape”, I’m referring to hyper-capitalism. This isn’t some ambiguous slur thrown at capitalism, but refers specifically to the coalescence of neoliberal capitalism and the digital revolution. It’s a globalized capitalism that expands outwards across the globe, and inwards, by treating attention as capital and re-designing human perception according to the logic of capital.

I made this sketch to explain visually:

By expanding outwards and inwards, across both space and time, hyper-capitalism defines and monopolizes our evolutionary and adaptive environments in the 21st century.

This means that, as we adapt and respond to our lived environments, we’re increasingly adapting to the conditions of hyper-capitalism. More than any economic system of the past, it conditions the kinds of humans we’re becoming.

How hyper-capitalism expands across physical space is straightforward enough. All public spaces devolve into advertising zones and business plazas. Cities are designed by and for capital, rather than people. How it expands across time is fascinating.

Here’s another few paragraphs on this dynamic, describing how capitalism creates free time in order to appropriate & commodify it:

Here’s how it works: the profit motive drives innovation that creates technological progress and improves productivity. Increasing productivity decreases the necessary production time for existing goods and services, creating surplus time. But capitalism cannot recognize surplus time as inherently valuable. Value is only measured, only shows up in the calculus of capitalism, once it generates a quantifiable return. So that surplus time is then reinvested back into the production process, creating surplus value, or increased revenues that show up on the accounting sheets. Cyclically generating surplus value is how capitalism sustains growth.

By decreasing necessary labor time, more surplus labor time is generated that can be reapplied back into the production process. Surplus labor time reinvested back into production generates surplus value - increasing the labor input to production increases the value created.

Capital depends upon this surplus labor time to feed the recursive cycle of growth. This is why predictions of 15-hour work weeks from luminaries and economists alike, from Bertrand Russell to Keynes, always fall flat. The time made available by new technologies is always reclaimed by the logic of capital. “Capital is interested in the expansion of only one type of unbound time,” writes political economist William James Booth, “namely, surplus labor time. More briefly, we might say that capital frees time in order to appropriate it for itself.”

Another diagram:

All time is mined as a source of value for the growth of capital. As all time warps towards commodity logic, we follow. The ‘self’, as subjectivity ensconced in monopolized time, becomes commodity. The pure commodification of time is the total commodification of the self.

But we can invert this logic to understand why policies like UBI can intervene in the production process.

By securing decommodified time for all in the form of unconditional income, UBI enables behaviors, relations, and projects - ways of living - that transcend the logic of capital. Greater diversity is introduced into how we might spend our time. Since the economy is a system we actively design, we’re given a ‘way in’ to participate in the process of our own development. More than ever before, we have agency in designing the environments that recursively redesign us.

…

I really look forward to sharing this essay - though it’s more like a short book. If you read this newsletter and we jive on topics of interest, you might enjoy it. It’s due to be published around 5/11, depending on how life unfolds.

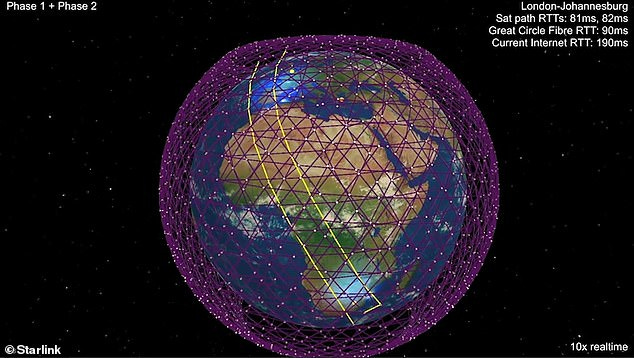

The Satellite Layer of the Atmosphere

This is a map of satellite connectivity encapsulating the earth. Looks like an actual layer of the atmosphere (from this great little essay on telecommunications technology and capitalism):

Want to be a Chinese civil servant? Write poetry!

I read a book of Mao Zedong’s poetry the other day (yeah, strange times). From the translator’s introduction, I learned that part of the exam to become a civil servant in old China required that hopefuls demonstrate their ability to write poetry. Poetics was a prerequisite for civil service. Wild.

Complex Environments, Generative Identity

In one of those poorly-formatted-but-brilliantly-insightful internet documents, the author explores how complex environments and choices give us the opportunity to generate ourselves, while standardized, monotonous environments thwart our capacities.

If two genetically identical mice grow up in standard little laboratory boxes with no complexity, no choices, just the same old dull thing all the time, they remain two little identical, bored mice.

But if the same genetically identical mice grow up in a large and varied environment, “small differences in their experience will affect cell growth in their brains, leading to large differences in their exploratory behavior as they age.”

They differentiate. Complex environments inspire exploratory behavior, while standardized, dull environments leave us undeveloped.

“If our environment restricts our choices, our becoming human is thwarted, the way rats' potentials weren't discovered when they were kept in the standard little laboratory boxes. An opportunity to be complexly involved in a complex environment lets us become more of what we are, more humanly differentiated.”

Slinging an absolute zinger, the author writes:

“Enrichment and deprivation have very clear biological meaning, and one is the negation of the other.”

He applies this to society: “possible the most toxic component of our environment is the way the society has been designed…Our culture reinforces routinized living.”

This is how I think of economics. We’re all living inside these laboratory boxes. Economic arrangements form the interior walls that create - or block - various pathways and possibilities. How do we design these environments so that everyone inside is enriched, given the maximum opportunity to generate differentiation? How do we design our environments to inspire exploratory behavior?

There are some clear parallels. ‘Money doesn’t buy happiness, but poverty buys misery’, the saying goes. Well, money doesn’t buy generative identity, but poverty certainly prevents it.

If you want to read that whole article, which I highly recommend, here it is.

That’s it.

As always, you can respond directly to this email with thoughts or suggestions, or reach out on Twitter. Let’s start a conversation.

If you have a friend who might enjoy this newsletter, consider sharing the link. The more people on this network, the more possibilities we can cook up.

Until next time,

Oshan