Mind Matters

The Catch-22 of Economics & Education

Mind Matters is a newsletter about contemplative philosophy, economics, and the bountiful absurdities of being alive. If you’re reading this but aren’t subscribed, you can join here:

Dear fellow humans,

A few new things to share before settling into the newsletter.

I recently went on two podcasts to discuss my essay on UBI & the Capitalist Production of Consciousness.

On Joe Wells’ podcast, our conversation had a pragmatic flavor. We discussed some specifics of UBI, taxes, capitalism, and what Jack Kerouac’s alcoholism means for my productivity habits. You can find our conversation here.

On Andrew Taggart’s Youtube channel, our conversation had a more philosophical, spiritual vibe. We explored what UBI has to do with the development of consciousness, how de-commodifying time can combat hyper-capitalism, and cultural evolution. That conversation lives on Youtube, here.

And finally, I published my latest Musing Mind Podcast with Michael Brooks. We discussed what economic systems and policy have to do with consciousness, compared UBI with a federal jobs guarantee, and explored the 21st century pursuit of anti-fragile localism balanced with globalized cooperation and solidarity.

Ok, sorry for the long intro. In we go.

Of Leisure, Labor, Play, and Pathology

I want to tell you two brief, parallel stories:

The decline of leisure and the rise of workism

The decline of play and the rise of psychopathologies in children

Each is fascinating on its own. But I also suspect they’re deeply interconnected. Together, they tell a sweeping cultural story about how educational and economic institutions coevolve.

Specifically, a reading of Peter Gray’s work on the decline of play can help answer a question I’ve been chewing on:

Why did we so suddenly change our cultural tune from thinking 15-hour workweeks would liberate us all to more deeply realize our own humanity, to thinking anything less than 40 hours a week would leave too much leisure time, and cause sociological decay?

Why, in other words, did leisure time fall from being seen as the concrete manifestation of civilizational progress, to a problem that must be avoided at all costs?

1. The Decline of Leisure

The beginnings of Industrial capitalism, like the early days of settled agricultural societies, were brutal. People worked 70+ hours per week in unthinkable conditions.

By 1830, a growing labor movement successfully connected abstracted ideas like “freedom” and “progress” to steadily decreasing the work hours. For the next 100 years, the reduction of the working week reigned as the concrete manifestation of progress under industrial capitalism.

I call this the expanding leisure hypothesis. By the early 20th century, it was nearly taken for granted that innovations would continue improving productivity. New technologies would allow us to continue scaling up outputs while scaling down human labor inputs. Wages would remain steady, or even rise. Cultural luminaries from Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Bertrand Russell, John Maynard Keynes, and especially the creators of the futuristic sitcom The Jetsons, believed economic progress would inevitably lead to shorter working weeks. Everyone would enjoy more time for leisure, play, and cultivating the ‘art of living’.

Here’s a common poster from the time:

In a letter to his wife, John Adams wrote of a two-generation timeline whereby his grandchildren would be free to devote their lives to intrinsically motivated leisure activities:

“I must study Politicks and War that my sons may have liberty to study Mathematicks and Philosophy. My sons ought to study Mathematicks and Philosophy, Geography, natural History, Naval Architecture, navigation, tion, Commerce and Agriculture, in order to give their Children a right to study Painting, Poetry, Musick, Architecture, Statuary, Tapestry and Porcelaine.”

A similar vibe is found in Keynes’ famous essay, Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren, and the writing of Walt Whitman.

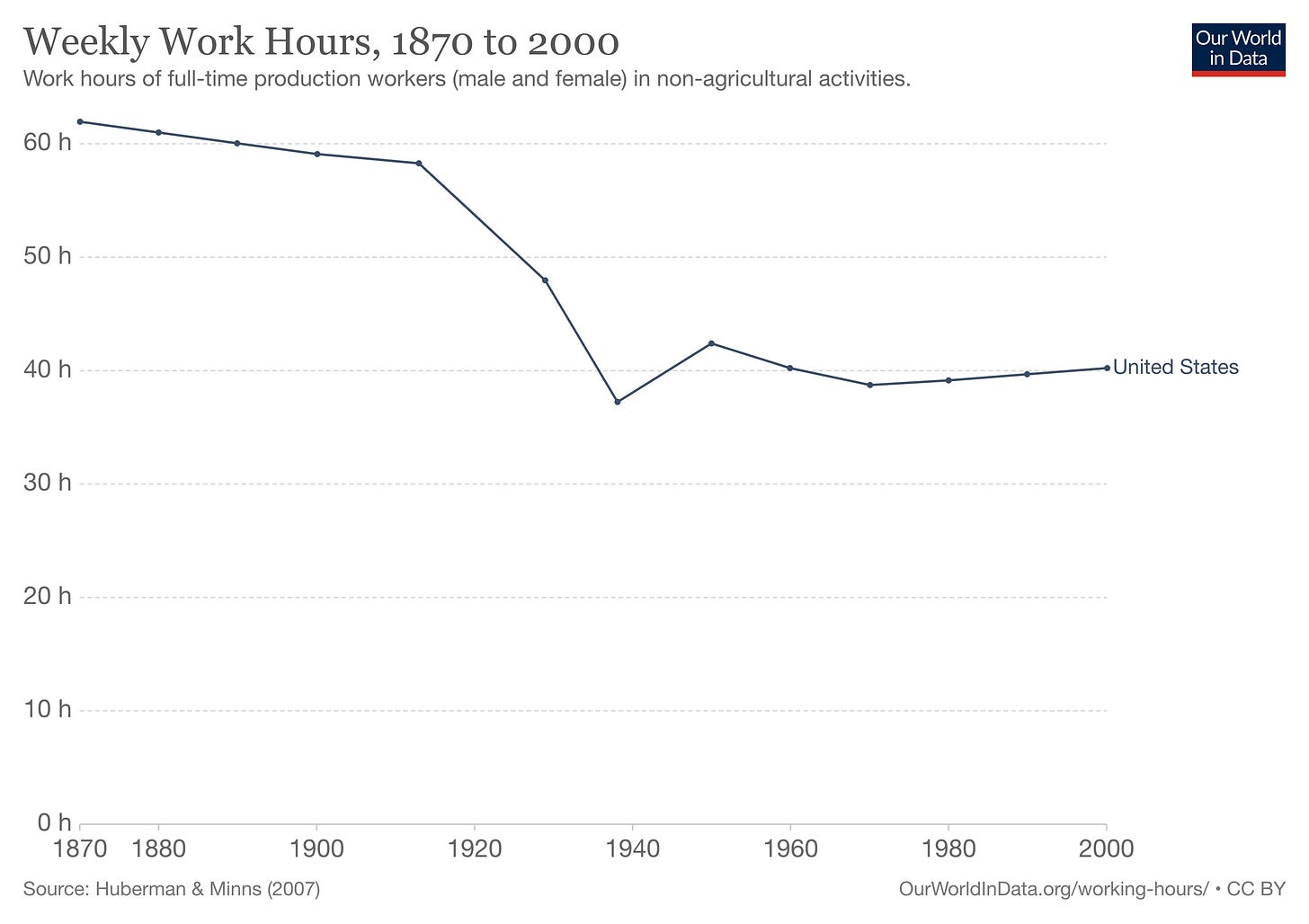

From 1830 - 1930, this story played out. Average working weeks declined from 75 (1800), to 65 (1870), to 50 (1929), down to 37 (1938).

But following the Great Depression and World War 2, the expanding leisure hypothesis fell apart. The fight for shorter hours became the fight for higher wages. The fight for leisure became the fight for full employment.

By the 1960’s, the cultural tide pulled a full 180-degree inversion. In 1964, the great science fiction writer Isaac Asimov was asked to imagine the world of 2014. He concluded his predictions with a great fear: the disease of boredom. It would spread and intensify as automation progressed. “Enforced leisure” would wreak “serious mental, emotional, and sociological consequences.”

But it was probably the U.S. Department of the Interior that most clearly framed the flip:

“Leisure, thought by many to be the epitome of paradise, may well become the most perplexing problem of the future.”

By the 1980’s the inversion was complete, like a clock hand moving from 12 to 6. Average working hours began increasing. ‘Progress’ was no longer conceived as shifting the balance of our time from labor towards leisure. Freedom from work became freedom through work. Derek Thompson describes this new religiosity of work as workism. Work, rather than leisure, became the means of “identity production”:

"The economists of the early 20th century did not foresee that work might evolve from a means of material production to a means of identity production."

Today, we’re still riding those same cultural patterns. Working time is increasing and wealth is concentrating (so that it affords more and more capacity for leisure to fewer and fewer people).

The historian Benajmin Hunnicutt, who devoted most of his professional life to studying this mysterious inversion of our attitudes regarding leisure, came to a simple conclusion: nationwide amnesia.

“I have come at last to the simple conclusion that one of the most important reasons for the end of shorter hours, the recent decline of leisure, and the substitution of the rhetoric of perpetual need for the traditional language of "abundance" is something like a nationwide amnesia.

We have forgotten what used to be the other, better half of the American dream. In our rushing about for more, we have lost sight of the better part of freedom-of what Walt Whitman, with so many others throughout American history, called Higher Progress."

But, by turning to Peter Gray’s work, I think there’s far more to this story.

We didn’t just forget shorter working hours and the leisurely promise of higher progress. We evolved. Culture evolved. We became different kinds of human beings, thanks to different institutions and norms that shaped our early lives. Just as growing teenagers need to purchase new pants to accommodate their lengthening legs, our culture developed new stories of progress to match our developmental changes.

In short, the decline of play eroded our capacities to use leisure well. The newfound fears of leisure that erupted in the 1960’s were based in observational fact: the latest generation of human beings were less equipped than ever to thrive with more leisure time.

2. The Decline of Play and the Rise of Psychopathologies in Children

Leisure is to adults what play is to children. The turning of the cultural mood against leisure might not have been an entirely ideological change. It could be a product of what the psychologist Peter Gray calls the decline of play and the rise of psychopathology in children.

Historians of play (yes, they’re real) refer to 1900 - 1950 as “the golden age of unstructured play”. Play is an intrinsically motivated, unstructured behavior, "not consciously pursued to achieve ends that are distinct from the activity itself.” As Gray documents, since the dawn of our species, play has always served a crucial role in healthy psychological development. Play, Gray writes, is how children develop “intrinsic interests and competencies.”

The flip side: without sufficient play, children do not develop intrinsic interests and competencies. They lose the capacity to self-regulate and govern behavior. In order to avoid boredom, anxiety, and idleness, they increasingly require externally imposed structures, goals, and rules. Declining intrinsic competencies turns leisure time into more of a problem.

From 1955 onward, children began to play less and less. Gray cites two factors: the media, and meritocratic pressures to get ahead early in life.

First, media and the news. Since the 1990’s, the dangers of unsupervised children outside (abductions, molestations, or murders) declined. But the news sensationalizes these crimes. In line with the availability heuristic, our brains tend to over-represent cases we’re more familiar with. The more crime we saw, the more likely we believed it to be, despite evidence to the contrary. Parents stopped letting their children play outdoors without supervision, and our public spaces grew less and less hospitable to play.

Second, meritocratic pressures drove parents to structure more of their children’s free time. The earlier you start cramming for the SAT, the better score you’ll get, the better school you’ll get into, and the better shot you’ll have at securing a living. From 1981 - 1997:

Time spent in school rose 18 %

Time spent doing schoolwork at home rose 145 %

Time spent shopping with parents increased 168 %

During the exact same time period that play-time declined, psychopathology rates increased. Gray makes the case for not just a correlational, but causal connection between the two.

The role of play in developmental psychology cannot be overstated. Gray surveys its role in:

Developing intrinsic interests and competencies

Decision making, problem solving, and self-control

Regulating emotions

Generating egalitarian approaches towards relationships (he speculates that the reason most hunter-gatherer societies were egalitarian is that children and teenagers were always free to play from dawn until dusk, every day.

Experiencing joy

The egalitarian bit is wild. Here’s a quote at length, if you want more context:

Anyway. Gray argue this relationship goes beyond correlation. The decline of play is causally related to the rising levels of psychopathology we see today:

Gray concludes:

“Somehow, as a society, we have come to the conclusion that to protect children from danger and to educate them, we must deprive them of the very activity that makes them happiest and place them for ever more hours in set- tings where they are more or less continually directed and evaluated by adults, settings almost designed to produce anxiety and depression.”

[If you dig any of this section, consider reading his paper. It’s really good]

Putting It All Together

So what does the decline of play have to do with our rejection of the expanding leisure hypothesis?

Recall: the pivotal time period was between 1964 - 1980. That’s when our social, economic, and political attitudes towards leisure definitively flipped.

Notice: This is right about the time that first generation of play-deprived kids entered adulthood. If 1950 - 55 marked the decline of that golden era of unstructured play, they would be 9 - 14 when Asimov predicted the disease of boredom, and 19 - 24 when the Department of the Interior released their statement inverting leisure from the image of paradise to the “most perplexing problem of the future.”

So here’s my hypothesis: the decline of leisure wasn’t an ideological shift, but an observational one. We didn’t just decide that all of a sudden, leisure would ruin rather than liberate humankind. We saw it. We saw that children and young adults lacked intrinsic competencies. We saw anxious, bored, depressed, narcissistic, extrinsically oriented young humans who we couldn’t possibly imagine would thrive if left to their own devices for most of their waking hours.

Leisure time evolved from an opportunity to a threat.

What Can We Do?

What to do about this mess is kind of a Catch-22: for children to play more, we need a culture that’s less extrinsically oriented. But for a culture that’s less extrinsically oriented, we need humans who’ve played more.

I’m sympathetic to Peter Gray’s conclusion - we need to let the kids play - but I don’t think it does enough to acknowledge the economic institutions that make this difficult.

We can’t just redesign schools and curriculums to foster play and intrinsic motivation if all those kids still need to graduate and get the same old jobs in the same old world. Our system is not designed for intrinsic motivation. School is becoming so extrinsically oriented precisely because economic anxieties & realities are so demanding. One can’t meaningfully change without the other.

Put differently: Education reform is an economic problem, and economic reform is an educational problem.

It should come as no surprise that I think a few well-designed economic policies - basic income, universal healthcare, and codetermination (for starters) - could function as catalysts for a spiraling process of reform. Beginning to lift the economic burden affords more space and time in our lives to experiment with intrinsically oriented behaviors. But I’m not well-versed enough on the educational side of things.

If you have any thoughts on this Catch-22, comment below!

I Got a Kitten

Here’s a twist: a new creature entered my life recently. Meet Tiru (short for “Tiruvanamalai, among Avery & I’s favorite spots in Southern India):

I suspect she might become my guru of leisure, showing me the ropes.

Comments & Community

As the newsletter continues to grow, I’m receiving more and more thoughtful responses, leading to some really wonderful email conversations. This is great, but I’m wondering if we might have enough people here to have these conversations collectively, open to all.

Substack is also growing, and they keep improving their features. They seem to have a pretty solid community commenting situation going on. So when appropriate, I’ll close each newsletter off with a question. As always, you can still reply to me privately.

Or, to leave a public comment: view the newsletter on Substack’s website, rather than in your email browser (click here), scroll to the bottom of the letter, and write your comment in the comment box (it won’t let you comment unless you’re subscribed). I’ll always check and respond - but so can others. Which is good, because judging from the emails so far, there are readers on here far more interesting than I am.

The Question: What kind of sense can we make, or what can we do, about the above-mentioned Catch-22:

To change the economy we need to change education, but to change education we need to change the economy. How and where do we begin?

Looking forward to your thoughts in the comments below!

That’s It

As always, you can respond directly to this email with thoughts or suggestions. Or reach out on Twitter. I’m here for conversation & community.

If you have a friend who might dig this newsletter, consider sharing it. The more people on this network, the more possibilities we can cook up, and the more time I can devote to these projects.

Until next time,

Oshan