Hey Folks,

I’m excited to share a new podcast episode - The Basic Income Episode with Karl Widerquist. Karl has over 40 years of experience studying basic income, earning two phD’s along the way.

I’ll dig into more detail below, but our conversation explores, among other things:

The relationship between basic income and freedom

How much UBI costs, and how to pay for it

Differences between UBI and a negative income tax

The free development of each is the condition of the free development of all

Here’s a fun double quote I came across. The first is from Charles Eisenstein’s book, Sacred Economics, in a section where he’s using the work of Christopher Alexander:

“Christopher Alexander lays out fifteen such principles in his profound book The Nature of Order. These fifteen fundamental properties characterize both natural systems and sublime works of architecture and art. They include levels of scale, strong centers, positive space, local symmetries, deep interlock and ambiguity, boundaries, roughness, gradients, and many others. But the key to his conception of wholeness, order, and life is the concept of centers: entities that, like elements, add up to create the whole but, unlike elements, are themselves created by the wholeness. ‘The wholeness is made of parts; the parts are created by the wholeness.’ Anything that has the quality of aliveness will be composed of centers within centers within centers, wholenesses within wholenesses, each creating all the others.”

The second is from the philosopher Roy Bhaskar, who’s later work attempts to synthesize elements of contemplative practice (specifically, the visceral experience of non-duality) with the philosophy of critical realism:

“The philosophy of Meta-Reality describes the way in which…the free development and flourishing of each unique human being is understood to be the condition, as it is also the consequence, of the free development and flourishing of all…to quote Marx’s vision of it, ‘the free development of each is the condition of the free development of all’…”

I love these parallels between Eisenstein’s riff on wholes being composed of wholes, distributed networks of centers creating centers, each whole in themselves but also contributing towards a larger wholeness, and Bhaskar’s bit on the free development and flourishing of each human being both the condition and consequence of the the free development of the collective. There’s a symmetry there, just out of my linguistic reach..

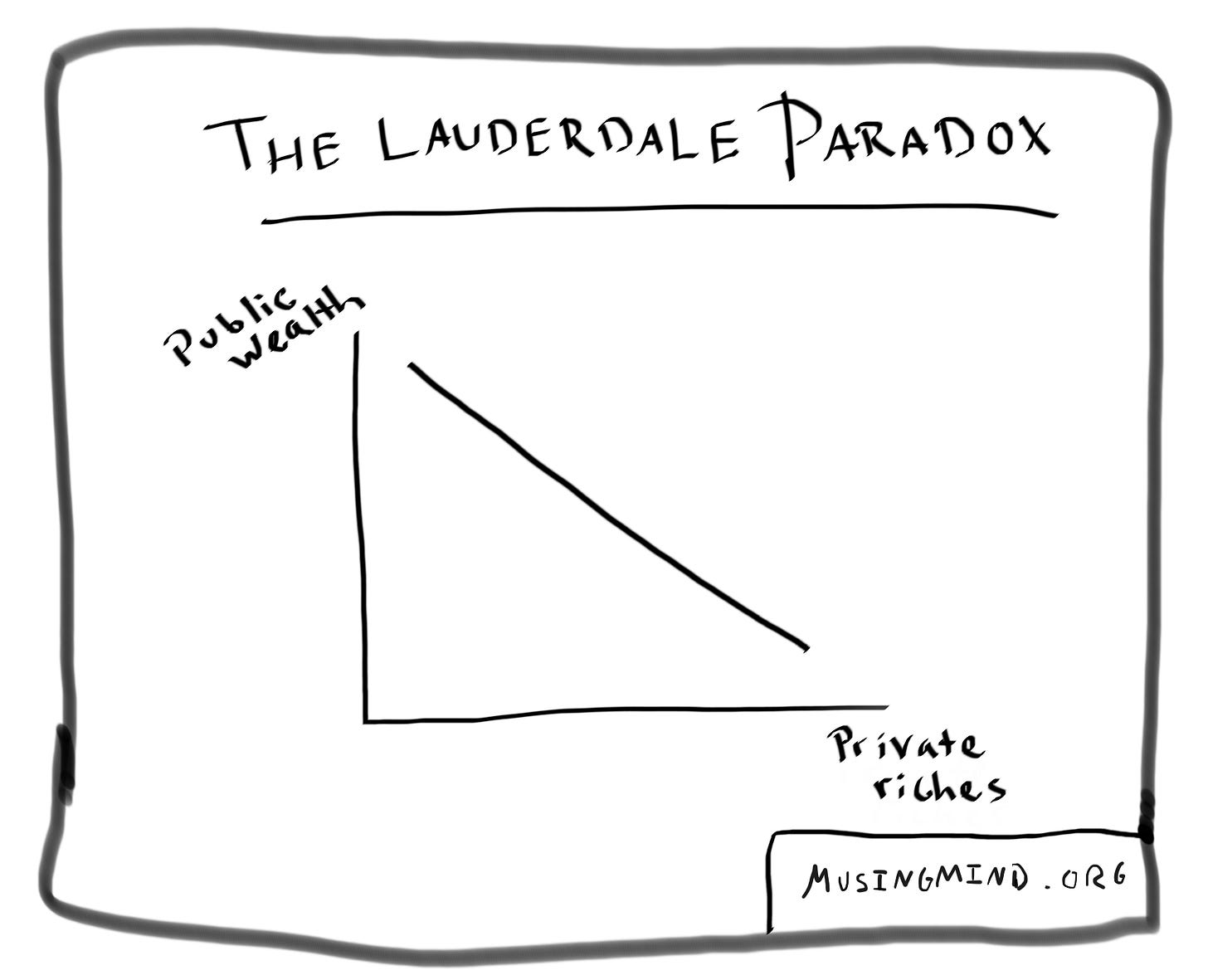

The Lauderdale Paradox

I found this paradox in a fantastic paper by Jason Hickel, an economic anthropologist at the London School of Economics.

The Lauderdale Paradox was coined in 1804, by the 8th Earl of Lauderdale, James Maitland. Maitland published a book called Inquiry into the Nature and Origin of Public Wealth and into the Means and Causes of its Increase.

Titles were wild back then.

His book posits an inverse correlation between “private riches” and “public wealth”, finding that one does not increase but at the expense of the other.

“A long view of the history of capitalism reveals that growth has always depended on enclosure. The Lauderdale Paradox first articulated by James Maitland holds that an increase in ‘private riches’ is achieved by choking off ‘public wealth’. This is done not only in order to acquire free value from the commons but also, I argue, in order to create an ‘artificial scarcity’ that generates pressures for competitive productivity.”

- Jason Hickel

The lauderdale paradox also provides an interesting critique of conflating GDP growth - however adjusted for ecological and inequality concerns - with progress. GDP only rises alongside private riches - economic transactions where owned resources are bought and sold. It has no mechanism to account for the value of public wealth, no way to measure or incentivize a growth of common resources everybody has equal and abundant access to.

“Indeed, our society’s obsession with GDP growth as the primary public policy objective reveals the entrenchment of the Lauderdale Paradox as political common sense, the ultimate triumph of enclosure: the growth of ‘private riches’ has come to stand in for Progress itself. Meanwhile, conveniently – and tellingly – there is no indicator that charts the concomitant collapse of public wealth.”

Which raises the question, what metrics exist that tie progress and public wealth together? GDP sets progress and public wealth (owned by everybody, and therefore nobody) at odds with each other. But if we are to abandon artificial scarcity as the motivating force of economic expansion and seek an economic environment of abundance, we’ll need metrics that realign progress with public wealth.

“The only way to resolve the Lauderdale Paradox is to reverse it: to reorganize the economy around generating an abundance of public wealth even if doing so comes at the expense of private riches. This would liberate humans from the pressures generated by artificial scarcity, thus neutralizing the juggernaut and releasing the living world from its grip.”

I cannot recommend Hickel’s paper enough, titled Degrowth: A Theory of Radical Abundance.

New Podcast Episode: The Basic Income Episode with Karl Widerquist

This episode is long - I wanted to cover a lot of ground.

We began with the abstract - how basic income relates to equitable freedom and creating a just society. Next, we pivoted into the details:

How much does UBI cost

How can we pay for it

Why is UBI preferable to a negative income tax

Do we need growth, degrowth, or are these unhelpful frames?

I had Rutger Bregman ringing in my ear while Karl and I spoke.

When Rutger spoke at the most recent Davos Economic Forum, his message was clear: we need to talk about taxes. Taxes, taxes, taxes.

So Karl & I covered all kinds of taxes - land value taxes, capital gains, marginal tax rates, wealth taxes, to name a few.

It was a delight speaking with Karl, who’s both a passionate, and rigorous, supporter of Basic Income. Although I think I’ll have to do a Basic Income Episode pt. 2 with someone more skeptical - though equally rigorous - of UBI to round out the debate.

Here’s our conversation. The show notes on the podcast page have a detailed outline of what topics were covered, at what time marks.

News from Contemplative Neuroscience

As neuroscientists are getting better and clearer looks into the brains of meditation practitioners, we’re finding fascinating results (and confirming a lot of ancient intuition).

A recently study published in Frontiers of Human Neuroscience added a new layer of insight to our scientific knowledge of the meditating brain.

Whereas much of the contemplative neuroscience literature studies mindfulness meditation, this study looks into a more disciplined form of meditation known as Jhāna meditation. Jhānas are known as states of deep concentration, or meditative absorption.

They found that Jhāna states have radically different neural correlates from less focused forms of meditation:

“While remaining highly alert and “present” in their subjective experience, a high proportion of subjects display “spindle” activity in their EEG, superficially similar to sleep spindles of stage 2 nREM sleep, while more-experienced subjects display high voltage slow-waves reminiscent, but significantly different, to the slow waves of deeper stage 4 nREM sleep, or even high-voltage delta coma. Some others show brief posterior spike-wave bursts, again similar, but with significant differences, to absence epilepsy. Some subjects also develop the ability to consciously evoke clonic seizure-like activity at will, under full control. We suggest that the remarkable nature of these observations reflects a profound disruption of the human DCs when the personal element is progressively withdrawn.”

Contemplative Practice Meets Cultural Theory

This is the most recent label I’ve given to my arena of interest. But “cultural studies” isn’t quite right.

Closer, perhaps, is how German sociologist Georg Simmel describes cultural sociology:

"the cultivation of individuals through the agency of external forms which have been objectified in the course of history".

And Wikipedia adds:

“Culture in the sociological field is analyzed as the ways of thinking and describing, acting, and the material objects that together shape a group of people's way of life.”

This is closer. By cultural theory, I mean the structures, systems, and institutions - external forms - that in-form, or encapsulate inside form, the lives of all participants in that culture. As far as what particular culture I mean, it’s getting more difficult, and impotent, to think of cultures as mutually exclusive.

As Zak Stein notes, at least since 1970, a singular world-system is emerging, a world-culture, of which global supply chains, international economic entanglements, and global media platforms are all connective tissue.

These complex cultural fibers are mostly invisible in our everyday lives, which means their influence operates at a subliminal level. It’s all too easy to ignore the unseen, but this probably isn’t the best strategy..

Blues Dispatch

I’m new to the music of Chris Smither, but it’s sublime. Blues meets folk at its best:

That’s It

As always, you can respond directly to this email with thoughts, critiques, and suggestions. Let’s start a conversation.

If you find any value here, you can visit my support page, or just share the newsletter with a friend who might enjoy it - http://musingmind.substack.com.

If you aren’t subscribed yet, here’s a button:

Until next time,

Oshan