Hello fellow humans,

I just published a full policy proposal for a negative income tax (a basic income that phases out as your earnings rise). I was surprised how little focus NIT receives relative to its counterpart, UBI, despite their achieving similar net outcomes. Most NIT writing dates back to the 70’s, when Nixon tried passing one. More info below, but if you’re into policy, I’d love feedback so I can improve the proposal.

Post-Covid Economic Manifestos

It’s a shame that crises often prove the best windows for meaningful change. I wish we could figure out how to make serious structural change without needing a tragedy to break us from the habituated normalcy that guards the status quo.

But here we are. There is tragedy, and there is opportunity.

This means that right now, history is happening somewhere. Ideas are being forged, refined, and circulated that will come to define the post-Covid world. Here, I’d like to explore three economic manifestos released in the past month that suggest possible futures I’d like to inhabit.

First, there’s the Democratizing Work Manifesto, signed by over 4,000 academics (including Thomas Piketty, Elizabeth Anderson, James Galbraith, & Jason Hickel). Second, the Berggruen Institute’s The Mutualist Economy: A New Deal for Ownership. And finally, the Dutch manifesto: Planning for Post-Corona: Five proposals to craft a radically more sustainable and equal world.

Democratizing Work

The Democratizing Work manifesto has 2 (ish) components:

Democratize firms by giving workers a direct voice, and voting rights, in company decisions via codetermination models

Decommodify work through a universal jobs guarantee

The -ish component is geared towards the environment. Rather than calling for any explicit environmental policies, they assume that democratic governance of firms will better align company incentives with environmental ones:

“A successful transition from environmental destruction to environmental recovery and regeneration will be best led by democratically governed firms, in which the voices of those who invest their labor carry the same weight as those who invest their capital when it comes to strategic decisions.”

My favorite idea in the proposal is how they propose the transition towards democratic governance: conditionality clauses for government bailouts in response to coronavirus.

If a firm wants a bailout from the government, and thus, from taxpayers, they would be required to meet certain conditions of democratic internal government:

“…our governments must make their aid to firms conditional on certain changes to their behaviors. In addition to hewing to strict environmental standards, firms must be required to fulfil certain conditions of democratic internal government.”

There’s something devilishly satisfying about using conditionality clauses here, the same ones that the IMF used to exploit capital markets in developing countries.

The IMF to developing countries: you want a loan? Remove protections and open your markets to us.

The government to Covid-crashing corporations: you want a bailout? Democratize your governance structures.

I have a lot of skepticism about a job guarantee (but Philip Harvey has some of the best pro-job guarantee research I’ve seen). At best, it’s a half-measure towards “decommodifying labor”. Yes, it’d probably be better than what we have now. It shields labor contracts from market fluctuations, puts pressure on private sector compensation to at least equal the public sector’s, and gives anyone who’s able to work access to a living wage.

But it still requires us to commodify our time in exchange for the means of survival. And what if more people ask for jobs than the government can provide? What if we have to put people to work doing absolutely meaningless bullshit? The dystopian possibilities are frightening.

A much larger step towards decommodifying labor, if we can afford it, would be to give people directly the money they need to meet their basic needs, without requiring them to exchange 40 hours a week for it (this was a theme of my long-form essay on basic income and social complexity).

The Mutualist Economy: A New Deal for Ownership

The Mutualist Economy proposal is an attempt to democratize the idea of an ‘ownership society’ proposed by George Bush. This is an old idea. For Karl Marx, too, the inequality of ownership was among the driving forces of capitalist injustice.

The Bush-era, neoliberal model of an ownership society thought that home ownership and retirement accounts would be enough to cut the middle class in on the fruits of capital growth (never mind low-income people).

This proposal offers a democratized vision for an ownership society suited to the technological landscape of the 21st century. They propose:

A sovereign wealth fund that owns equity shares in American companies to capture capital gains for the public.

Joint public-private ownership of government-funded patents (so that taxpayers who fund innovations see financial returns on their investments).

Public investment & savings banks.

“Baby bonds”, issued to citizens at birth, redeemable upon coming of age (say, 25 years old). Like an inheritance, but for everyone.

Guaranteed retirement accounts, meant as an improvement upon 401(k)’s, so that ordinary people can access higher returns, closer to those seen by wealthier investors.

The authors write:

“We contend that the central challenge of contemporary economic governance is to design new institutions of asset ownership that give ordinary people access to wealth creation at its source. Rather than wait for wealth to be produced in an unequal way, and then attempt to use tax policy to redistribute that wealth, our institutions should “pre-distribute” that wealth at the point of its production through the mutual ownership of wealth-producing assets.”

The proposal in its entirety is superb. If you can stomach economics, I really recommend reading it.

Planning for Post-Corona: Five proposals to craft a radically more sustainable and equal world.

This one is short and sweet. A single page document with 5 proposals and 170 Dutch academic signatures. In true manifesto form, their proposals are more like sentiments than actual policy proposals.

They call for:

Moving away from aggregate GDP as a useful metric, decomposing it into more nuanced, sector-specific growth and de-growth targets. For example, growth in clean energy and education is good, while de-growth in advertising mining, and private sector oil is good.

Progressive taxation of income, profits, and wealth that funds universal basic income, reducing working hours, and a strong social policy system.

Transitioning agricultural practices towards regenerative agriculture, biodiversity conservation, an emphasis on vegetarian food production, and fair labor conditions for agricultural workers.

Reduction of consumption & travel. They phrase this as: “a drastic shift from luxury and wasteful consumption and travel to basic, necessary, sustainable and satisfying consumption and travel”.

Debt cancellation, including for countries in the global south.

The first point, decomposing aggregate growth into sector-specific growth & degrowth targets, recalls much of Marianna Mazzucato’s insistence on “mission-oriented” growth. I can imagine a simple dashboard of indicators that show the growth and degrowth in particular industries.

It’s also interesting to tie basic income together with a reduction of working hours. This was a point emphasized by André Gorz in his Critique of Economic Reason (a book I cannot recommend enough, if you don’t mind dense writing. I collected my favorite passages here).

Gorz’s primary objective is the reduction of working time without reducing wages. But he recognizes this will be difficult and put undue strain on businesses. So he suggests framing basic income as a “second check”. As working hours dwindle, wages are proportionally reduced. Workers then receive the second check, which makes up the difference in lost wages.

He sees these two policies, working in tandem, as a strategy to “enliven society”:

"And lastly, I know that a policy of a staged reduction in working hours, accompanied by a guaranteed income, cannot fail to enliven thinking, debate, experimentation, initiative and the self-organization of the workers on all the different levels of the economy and therefore to be more generative of society and democracy than any social-statist formula. This is the essential point: that control over the economy should be exercised by a revitalized society.”

Basic Income, Scenius, & Brian Eno

Turns outs, when the musician Brian Eno coined the term scenius - genius as a property of a collective scene, rather than a single heroic individual - he was at a talk on basic income [I learned this from Packy McCormick, who wrote a great essay on scenius].

Eno says that the concept of basic income is the closest thing he’s heard to enacting the kind of future he’d like to live in. He suggests that one of the biggest obstacles to cultivating scenius - “Scenius stands for the intelligence and the intuition of a whole cultural scene. It is the communal form of the concept of the genius” - is that people have to work jobs and earn a living. By this, he means people have to focus on things other than where their inherent curiosities point them.

This is akin to what I wrote about Marx’s idea of exchange value in the last newsletter. If we’re working just for the paycheck, with no inherent interest in the thing itself we’re doing, there’s an alienation that arises between us and our work that drains vitality.

This is why I tend to think about basic income in terms of progress, rather than justice. We’ve always had to sacrifice some portion of our waking hours towards doing what we must to maintain our survival and place in society.

Basic income, just like reducing the working week without reducing wages (or via Gorz’s second check), puts a dent in this historically stubborn necessity. It opens space for people to put their time towards their curiosities. It would improve the social conditions for scenius to flourish.

Echoes of Emerson in Gorz

There’s a passage from André Gorz that mixes Eno’s vision for scenius with Emerson’s famous passage: “Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe?”

Gorz writes:

“For society is no longer to be found where it institutionally proclaims its existence…Society now only exists in the interstices of the system, where new relations and new solidarities are being worked out and are creating, in their turn, new public spaces in the struggle against the mega-machine and its ravages; it exists only where individuals assume the autonomy to which the disintegration of traditional bonds and the bankruptcy of received interpretations condemn them and where they take upon themselves the task of inventing, starting out from their own selves, the values, goals and social relations which can become the seeds of a future society.”

This is worth digesting. Where society says it is, it isn’t.

Society exists where individuals (or scenes) shed the bankruptcy of “received interpretations”, and take upon themselves “the task of inventing, starting out from their own selves”.

Now consider Emerson’s passage at length:

“The foregoing generations beheld God and nature face to face; we, through their eyes. Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe? Why should not we have a poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition, and a religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs? Embosomed for a season in nature, whose floods of life stream around and through us, and invite us by the powers they supply, to action proportioned to nature, why should we grope among the dry bones of the past, or put the living generation into masquerade out of its faded wardrobe? The sun shines to-day also. There is more wool and flax in the fields. There are new lands, new men, new thoughts. Let us demand our own works and laws and worship.”

What Gorz adds to Emerson’s vision is a Marxist analysis that recognizes the project of forging an original relation to the universe requires economic transformation.

If this kind of freedom is to extend beyond the privileged, and set across society in democratic fashion, it can only be achieved collectively. How?

A new deal for ownership that restructures capital flows and value creation so that all participants share in progress.

A democratization of work, so that workers both have, and feel, a sense of agency in their labor.

Progressive taxation that funds robust social programs, from basic income to healthcare, that decommodify our time. Because we need the kinds of robust social and technological innovations that scenius generates. Scenius flourishes in decommodified time.

Sound familiar?

A Negative Income Tax for the 21st Century

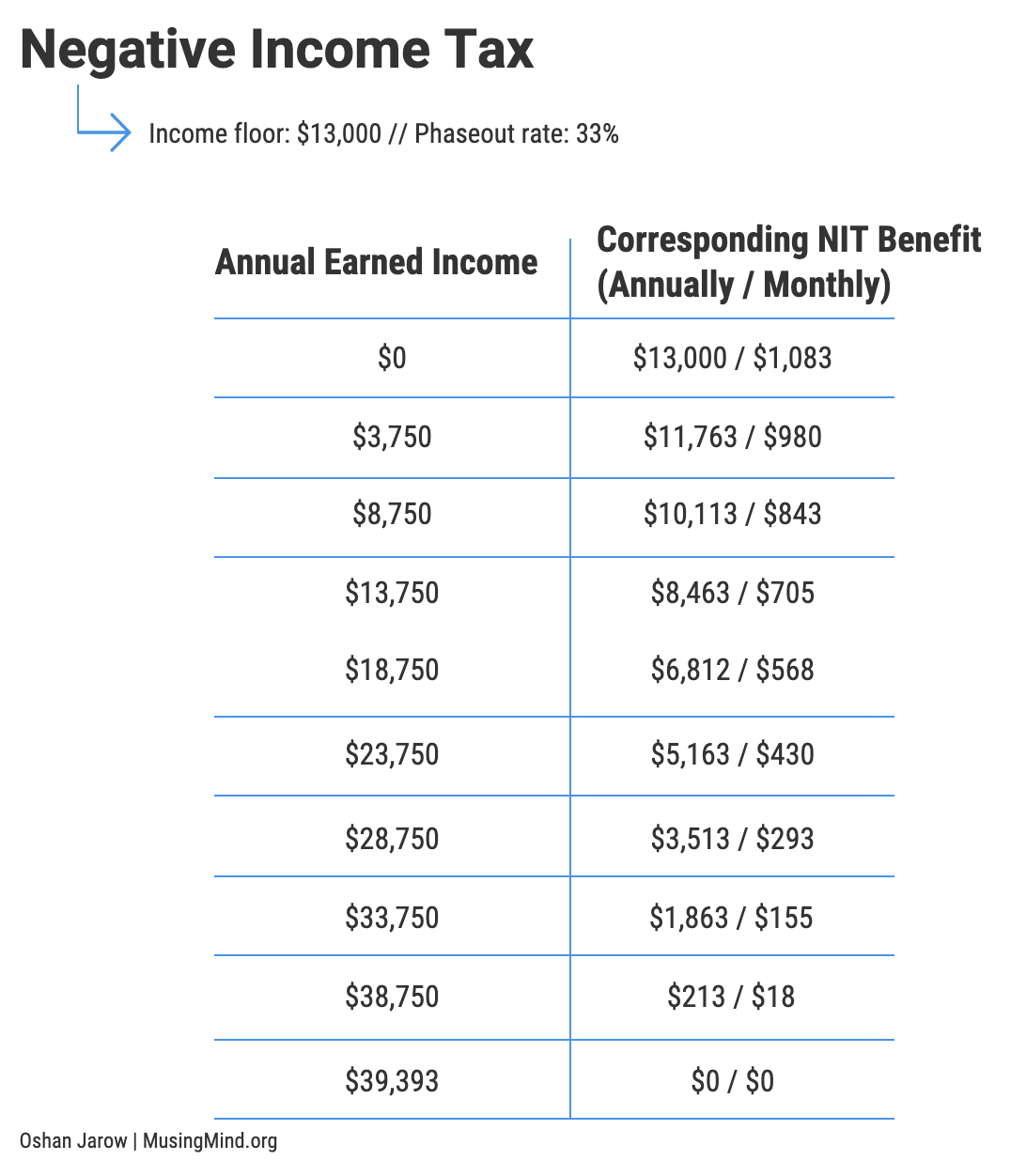

The proposal: a NIT with an income floor of $13,000 and a phaseout rate of 33%. This sets the breakeven point (earnings after which NIT benefits phaseout to $0) at $39,393.

This means if you earn $0, you receive $13,000 from the program. For each dollar you earn, you lose $0.33 cents of NIT benefit. I estimate the program’s cost at $855 billion, and include 3 full funding proposals.

The earnings/benefits relationship looks like this:

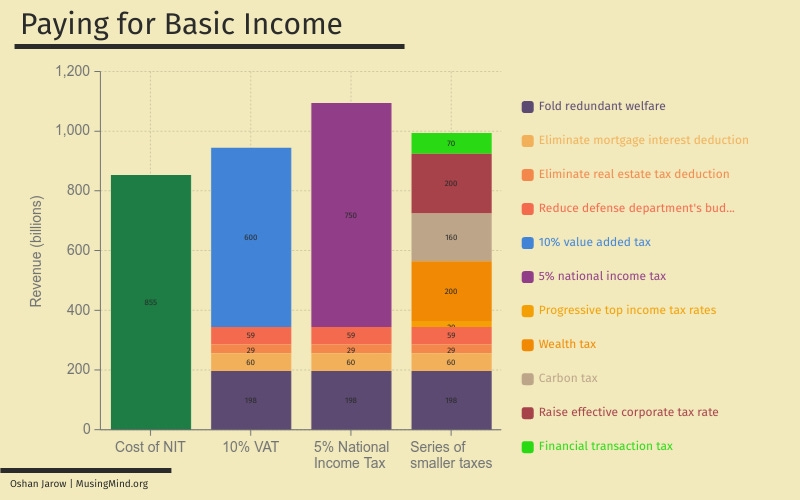

Even though my cost estimate is $855 billion, I set my funding target at $1.09 trillion - the highest cost estimate I found for a similar NIT.

I propose 3 funding options. Each uses a base of eliminating or reforming existing welfare and tax programs, yielding $346 billion. I then give 3 options to use new progressive taxes to raise the remaining $744 billion.

If you’re interested, you can read the full proposal here:

That’s it.

As always, you can respond directly to this email with thoughts or suggestions. Or reach out on Twitter. I’m here for conversation & community.

If you have a friend who might dig this newsletter, consider sharing it:

The more people on this network, the more possibilities we can cook up, and the more time I can devote to these projects.

And if you don’t already, you can join here:

Until next time,

Oshan

Testing