Where's all the economic value getting stuck?

Piketty, Rognlie, & George. Where's the money getting stuck?

Hi, I’m Oshan. This newsletter explores topics around emancipatory social science, consciousness studies, & together, the worlds they might weave. If you’re reading this but aren’t subscribed, you can join here:

Quick bits of news.

If you’ve been following my recent series on value theory and vitality, I recently published an essay with Return Magazine that condenses things into about 1,800 words. You can read it here.

Also, the next guest for the podcast is confirmed. I’ll be speaking with Christian Arnsperger, an economic anthropologist who wrote this synthesis of Ken Wilber’s integral theory and post-neoclassical economics. He’s sketching an integrally informed framework for what he – and Erik Olin Wright – would call an emancipatory social science. If you’re interested in his work, or in the conversation between integral philosophy and post-neoclassical economics, I’d love to hear any ideas/thought as I prepare.

Ok, in we go.

…

Economies Produce and Distribute Potential

Brian Massumi writes that “Capital, as movement of potential, is the quality of money as transformational force, the force driving the system’s becoming.”

Hold on to this idea: money’s quality as a transformational force, a fluid movement of potential, its patterns of ebbing and flowing slowly, rhythmically, comprehensively giving shape to the system’s becoming.

The US economy produces and circulates a lot of this fluid and transformational force – money – every year. Nearly $20 trillion in 2019 alone. Imagine it like this: every year, we raise a dam from deep within the forest that releases all that money, spilling out across the topologically complex forest floor. It does not flow evenly, but in tune with the terrain.

Just about every corner of the ideological spectrum agrees on one thing: too much of it is getting stuck somewhere. It’s pooling and accumulating, leaving other parts of the forest floor dry and barren.

But very few groups can agree on where, exactly. We’re left with a maldistribution of potential.

…

Wealth vs. Housing Prices: Where’s the Snag?

In 2014, the economist Thomas Piketty published Capital In the 21st Century, making a now-famous case that money is getting stuck with the wealthy, the infamous 1%. If you create two categories – labor and capital – and map how much of the country’s annual income is going to each, you’ll see that capital is absorbing more and more of the overall production of monetary value.

For Piketty, “capital” is basically synonymous with “wealth”. It’s a broad definition that includes things like stocks, cash assets, houses, land, intellectual property, and interest. As a result of capital’s gravitational pull on all the fresh money the economy produces, he argues, we’re speeding towards a historic imbalance of wealth and power that will undermine democracy, society, and any sensible notion of justice.

Then, in probably the most-cited critique of Piketty’s work, the economist (at the time, graduate student) Matthew Rognlie argued that Piketty’s simple division of the economy into capital and labor was too blunt to see where things are really getting snagged.

Instead, you need to divide the economy into three categories by separating housing prices as a distinct category from “capital”. Once you do, you’ll see that actually, the capital share hasn’t increased at all through the postwar era. What has increased are housing prices.

From Rognlie’s paper. Note that with housing separated out, the returns on the rest of the “capital” category seem to have actually decreased:

Piketty’s work is often mobilized to argue that the wealthy 1% are the snag where value is getting stuck, and the response should be a globally coordinated effort to tax wealth. Rognlie argues this is far too broad: if we want to mitigate inequality, our focus should be more specific, on housing prices.

…

Look to the Land

But not so fast! Georgism (the economic philosophy inspired by the 19th century political economist Henry George) argues that Rognlie is committing the same mistake he criticizes Piketty for: using too blunt a tool to really see where all this economic value is getting stuck.

As Lars Doucet has recently articulated, housing prices can further be broken down into land value and the value of buildings + improvements built atop that land. Now, we’ve split the economy into four pieces:

i. Labor

ii. Capital

iii. Buildings + improvements

iv. Land

With this new category, it’s argued that in fact, buildings + improvements aren’t driving up capital share either, they aren’t the source of the snag. Instead, after separating it out, you’ll find that land value is where the economic value production is disproportionately accumulating, like a secret basement filling with water.

Here’s Lars giving an overview (should start at 7:38):

…

Piketty vs. Rognlie

This is a compelling story. But as these things go, it isn’t that simple. Piketty mostly dismisses the Rognlie critique. Here he is in conversation with Tyler Cowen, who asked what he makes of it (should start at 19:44):

Piketty’s response is that real estate (including land values) isn’t responsible for driving up the top 1%, or 0.1%’s wealth portfolios, even if it is responsible for driving up wealth inequality more broadly. His focus is not on aggregate wealth inequality, but the distributional inequality, especially focused on what’s happening at the very top.

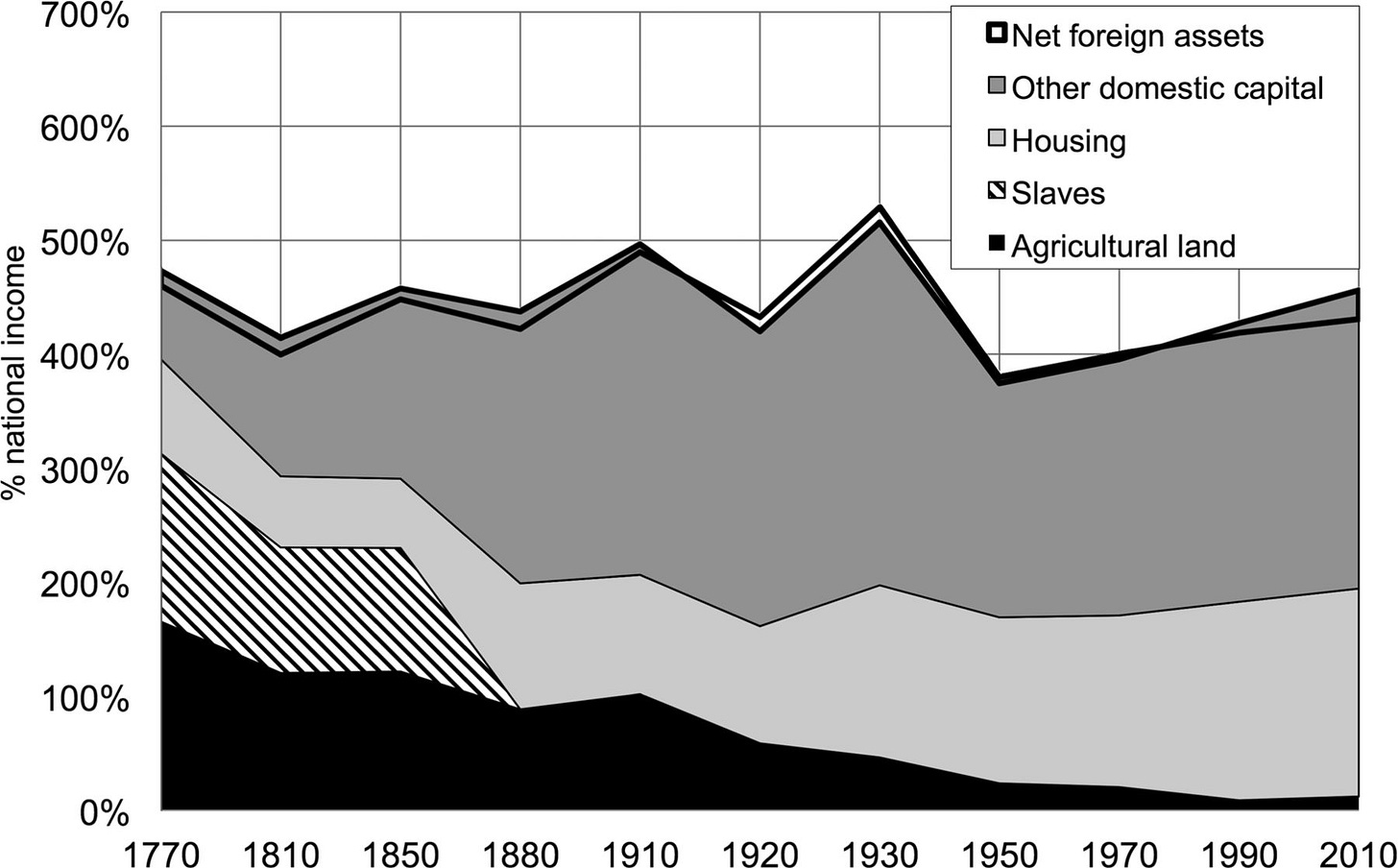

Again, he does agree that if you’re looking at aggregate wealth, real estate is a big deal, especially for the middle class. He references a paper where he & colleagues showed the decomposition of national wealth, confirming the magnitude of real estate (housing):

But if you’re interested in the distribution of wealth, with a focus on what’s driving up the portfolio’s of the world’s wealthiest people, Piketty argues that business/financial assets are far more significant than real estate.

…

What do you care about?

As one does when they’re burrowing into a rabbit hole, I took to Reddit, in the hopes of better understanding the contours of the disagreement between Piketty and Rognlie (the fact that I’m linking Reddit should convey that if you’re looking for definitive answers, I don’t have them).

One response seemed to locate a crux of the issue nicely:

“At the end of the day, poor people being as badly off as they are has much more to do with land than it has to do with the 1%. US billionaires have made $2 trillion since 2019 and some of that is justly earned, non-rent, although of course some is due to monopoly patents. US homeowners made $9 trillion just in 2021 and that is 100% rent.”

I think this puts the main point of divergence on display. Cowen, Rognlie, & this Reddit post are interested in aggregate wealth inequality. Within that context, land seems to be a more significant factor than financial assets.

But Piketty is interested in more than just aggregate wealth inequality. He’s also concerned about democracy, education, and justice. And people concerned about those things tend to – rightfully, I’d add – feel that what’s going on at the very top of the wealth distribution is very important, even if it isn’t the largest explanatory factor behind rising inequality overall.

…

Also, Rognlie’s numbers don’t look very Georgist

To confound things further, Rognlie’s numbers don’t really agree with the Georgist view. In his paper, Rognlie decomposed ‘housing’ into constituent parts, including separating land value out.

If you look at both lines for land, you’ll find neither are big contributors to the rising share of returns on capital. Instead, the key elements appear to be structures and equipment:

This discrepancy aside, even if Rognlie’s numbers aren’t very Georgist, their ultimate policy prescriptions are very Georgist-compatible. In his paper, he holds exclusionary zoning responsible for much of the rise in housing prices, and suggests that reforming them should be a primary focus for those interested in reducing wealth inequality.

Repealing exclusionary zoning is a practice that Georgists support (alongside land value taxation), and Piketty supports as well (alongside progressive wealth taxation).

The fact that there’s general policy agreement (or at least complementarity) among these disagreements raises an interesting question: why does this argument matter?

…

There’s a lot of harmony here

If society today made sense, maybe we’d just have Piketty, Rognlie, and Nicolaus Tideman (or Doucet, or whoever your preferred Georgist representative might be) all sit down in a room, bring their datasets, and arrive at some shared understanding. This would be a great podcast.

But, alas. In lieu of that, I’ve arrived somewhere that’s far from the bottom of the rabbit hole, but deep enough that I don’t feel much need to continue digging.

We should progressively tax wealth, regardless of whether or not returns to non-housing capital are driving up capital’s share of national income. There’s more at stake in historically concentrated wealth than inequality alone.

We should repeal & reform exclusionary zoning practices, regardless of whether it’s returns on land values, or buildings and structures, or other improvements that’s driving up housing prices. Exclusionary zoning places a stranglehold on urban development.

And we should implement land value taxes, because it’s one of the great mistakes of modern market economies to have gone on this long without doing so.

Each of these complements the other. The bickering that remains is not to determine which policies are necessary, but where they fall on the priority list, and how to strategically allocate resources towards their realization.

…

Economy as the conversion of potential into actual

The economy is a deterritorialized topology that gives shape and direction to the system’s becoming. And so, to our own. It's a socially constructed system by which we pattern the transformation of our potentials into actualities.

Each year, we produce great quantities of money, that transformational force that flows through the economy, its pathways given by the shape of the landscape. Labor digs the ravines and crevices. Tax policy sculpts the riverbanks and bends. Trees and objects populate the landscape according to land-use regulations. And vegetation – life – emerges most vigorously along the most watered pathways.

Capital, like water, is formless potential that molds itself to the topologies we have great agency in designing, and redesigning. This is how someone like Karl Marx could believe that given the right topologically constructed landscape, capital would flow, and accumulate, and burst straight through into its negation, into communism.

We are stewards of the landscape. Progressive wealth taxes, repealing exclusionary zoning regulations, and land value taxes are each symbiotic tools at our disposal. Our tools, used wisely, can create landscapes for more conviviality.

Let’s get to work.

Until next time,

Oshan.