Further notes on tripping alone

The history of the Western Model for psychedelic use tells the story of its own decline.

This missive elaborates on a recent piece I have out in Asterisk Magazine. You can read that here.

In what should come as a surprise to nobody, we in the West have developed an approach to using psychedelic drugs that goes against the major tenets of tripping honed by non-Western cultures for millennia.

Whether Shipibo or Santo Daime ayahuasca ceremonies, Mazatec psilocybin vigils, Bwiti ibogaine rites, Native American Church peyote use, maybe even the Ancient Greek kykeon-fueled Eleusinian Mysteries initiations, many cultures of psychedelic use often share in two pillars: people trip in community, and enmeshed in particular cosmologies of interpretation and healing, often with guides who freely, skillfully wield the responsibility of suggestion.

The major institutionalized approaches to psychedelics in the West, then, have us all tripping in historically peculiar fashion: alone, and under “non-directive” supervision.

Whether you’re tripping at a MAPS psychedelic therapy session using MDMA to treat PTSD, a Johns Hopkins clinical trial testing psilocybin as a trigger for mystical experiences, a swanky ketamine clinic in Manhattan on a depression diagnosis, or an adult-use psilocybin center in Oregon or Colorado for personal reasons — all these therapeutic, academic, and public models that bring legal psychedelic experiences to the general population, are built on the same pillars of solo trips and non-directive guidance.

I call this the ‘Western Model,’ and have a piece out in Asterisk Magazine detailing its philosophy, triumphs, and perils:

In the piece, I focus on a somewhat insidious quality of the Western Model. By concealing its own cultural bias under the pretense of neutrality, it nudges the psychedelic experience towards the values of individualism and autonomy, while foreclosing on the much wider panorama of psychedelic experiences that might arise from rituals that leverage community and suggestion. It smuggles a set of values, and through them, a frame of reference into the psychedelic business of breaking frames, thereby creating a subtle loom on which the pieces of the mind reassemble themselves. We are each alone, and individually responsible for making sense out of all this chaos.

More broadly: we should value the legal freedom to design our own psychedelic rituals, built around values of our choosing, rather than being corralled into one culturally-specific way of working with them.

But there’s a simpler question to track in all of this. If the Western Model of tripping is such a break from existing precedents, how did it come to be?

Why do we trip this way?

I touch on this in the piece a bit. But to make room for other points I wanted to make, and first-hand reports from my voyage to an ayahuasca church in Oregon, where I tripped with people who were mostly old enough to be grandparents and saw weird psychedelic bugs in my head, much of that history was left on the editing room floor. Here, I’d like to trace the history of the Western Model in more detail. Partly because it is an excellent, characteristically strange story.

But also, if you squint hard enough at recent stages of the Western Model’s development, you find a thread that frays just a bit more at each step. You find that telling the history of the Western Model contains the story of its own decline.

II. In which Captain Trips rejects hospital tripping

Why do we trip this way? The answer is surprisingly tractable. A thorough answer would be indistinguishable from a complete history of all creation. In lieu of that, we can begin the story in 1951, with the eccentric figure of Al Hubbard, who would eventually receive the nickname “Captain Trips,” on account of his habit of flying celebrities from Los Angeles to Vancouver to try LSD and then back.

Hubbard had been many things. A bootlegger, Catholic, science director of a uranium mining company, owner of a private island off the coast of Vancouver, a suspected CIA informant, and around 50 years of age, unhappy.

Adrift while hiking in the woods, he had a vision. As he told it to a friend, an angel appeared to him and said that “something tremendously important to the future of humankind would be coming soon, and that he could play a role in it if he wanted to.”

A year later, in 1952, he stumbled across a paper describing the effects of giving rats a newly developed drug called LSD. Sandoz Laboratories had been casually distributing LSD to psychiatrists since 1947, but there wasn’t all that much psychedelic fuss yet. Intrigued, he tracked down the study authors, got some LSD, and, well: “I saw myself as a tiny mite in a big swamp with a spark of intelligence. I saw my mother and father having intercourse.”

Clearly, seeing himself as a tiny mite and watching his parents have sex were just the signs the angel had meant. Hubbard emerged with a new mission: “to liberate human consciousness,” as he reportedly told Albert Hofmann, who first discovered LSD.

Hubbard was a man of many, if shadowy, connections. Various accounts have him procuring massive quantities of Sandoz LSD, from one liter to forty three cases to six thousand vials, a chunk of which he carried around with him in a leather satchel.

He became the sole distributor of Sandoz LSD in Canada, and miraculously secured an investigational permit from the FDA letting him conduct clinical LSD research in the US. Michael Pollan reports that Hubbard “would introduce an estimated six thousand people to LSD between 1951 and 1966, in an avowed effort to shift the course of human history.”

Around this time, there were few Western protocols for how to use LSD. Psychiatrists were generally just giving patients LSD as they would other on-site treatments: in rickety hospital beds under fluorescent lighting, caged in by sterile white walls, and surrounded by the discomforting palette of hospital sounds. Beeps, groans, emergencies.

This is also, by the way, where the “solo” aspect of the Western Model stems from. We trip alone because psychiatrists were in charge of distributing the initial supply of LSD, and the way that psychiatrists deployed medicines was on an individual basis.

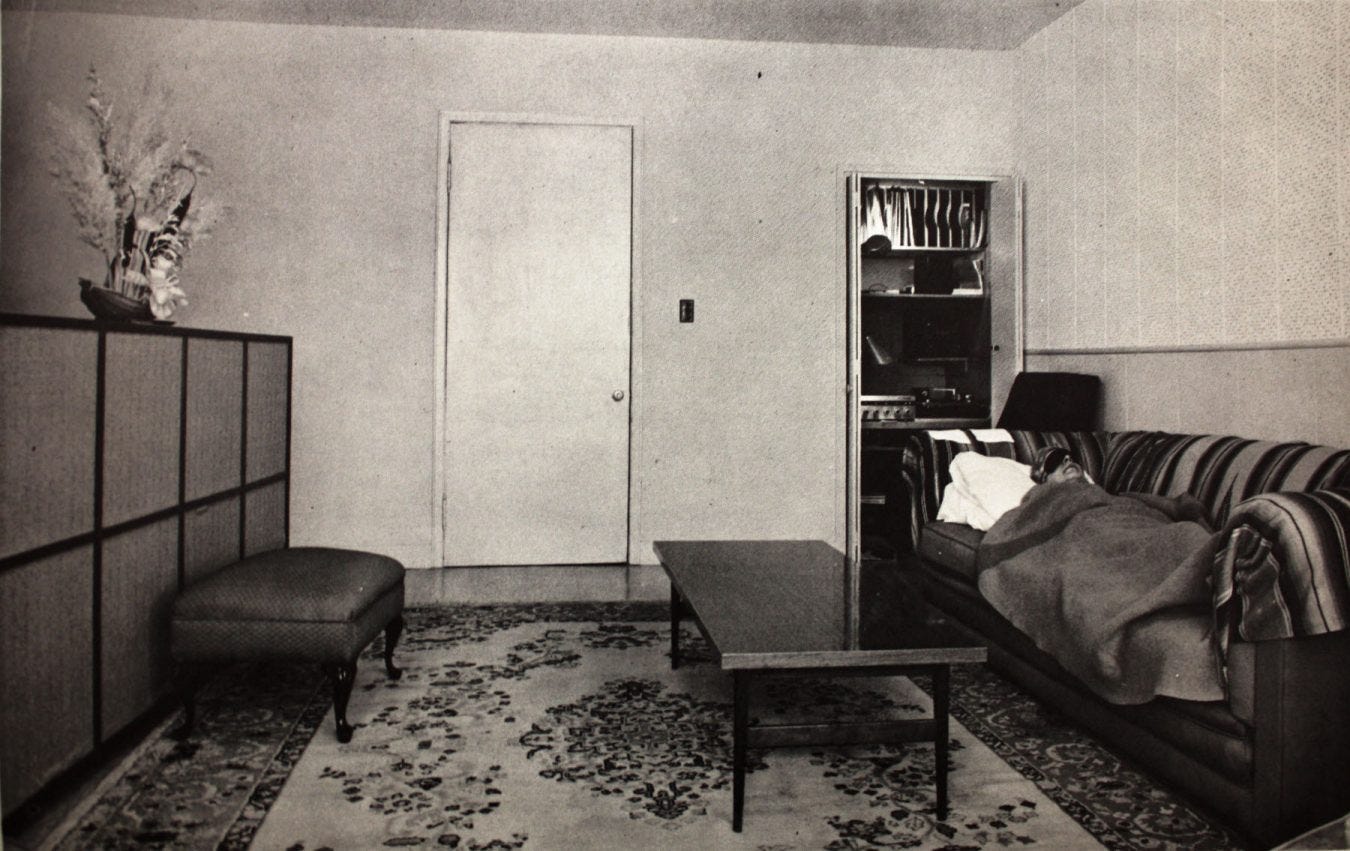

Hubbard championed the retrospectively obvious point that hospitals were no place to trip. He was one of the first Western psychedelic researchers to take “setting” seriously. So he established LSD treatment centers across California and Vancouver with rooms that felt more like living rooms than a hospitals. He scattered art along the walls, bouquets of roses on coffee tables, even diamonds were strewn about. He played classical music. He made sure no one was entering cardiac arrest nearby. This “comfortable living room environment,” as its often called today, was initially known as the “Hubbard Room.”

As one psychedelic researcher told Pollan: “This whole therapeutic regime, which is now the norm, should by all rights be known as ‘the Hubbard method.’”

III. In which Spring Grove Hospital formalizes the method

But Hubbard’s method, like his life, was informally orchestrated. He did not like working with formal treatment centers because they were charging north of $500 per LSD treatment (around $6,000 in today’s dollars). If he was going to help liberate human consciousness, $500 a pop wouldn’t do.

He continued seeding LSD experience across the land, from Aldous Huxley to engineers working in the early days of Silicon Valley. But the next step in the development of the Western Model would be one of institutional formalization. And that brings us to Spring Grove State Hospital outside Baltimore.

The “Spring Grove Experiment” was kicked off by psychologist Sanford Unger. He was aware of psychedelic research through his contact with the team at Hollywood Hospital in Vancouver, where work on using LSD to treat alcoholism had been ongoing. This was one of the Canadian centers that worked with Al Hubbard to devise their treatment protocol, connecting the Hubbard Method right to Spring Grove.

From 1955 to 1976, while hippies were riding in rainbow-painted buses dishing out LSD-spiked Kool-Aid, and the CIA was attempting to use LSD for mind control, Spring Grove kept up a relatively uncontroversial stream of psychedelic studies, mostly focusing on LSD as a treatment for addiction, end-of-life anxiety, and mystical or “peak experiences.”

In 1955, the first Spring Grove study gave LSD to patients with chronic schizophrenia. They tried using a double blind procedure, where study participants didn’t know who got the LSD and who got placebo. This, of course, did not work, and the blinding procedure was quickly abandoned. Even after a 1962 amendment made double-blind controls the gold-standard for drug research, both hospital staff and patients objected on ethical grounds. They wanted anyone who qualified for treatment to receive it (we still haven’t figured out how to blind psychedelic studies).

Psychedelic research at Spring Grove was housed in “Cottage 13” on hospital grounds, a two-story facility with two designated treatment rooms. Their approach was to use psychedelics as an adjunct to psychotherapy in treating various conditions, which in addition to the Hubbard Room decor, couched their method within existing clinical norms.

Patients received preparation sessions beforehand and integration work afterwards. They wore eye shades and headphones that played carefully curated classical music. A male and female supervision team, one a therapist and the other usually a nurse, was always present to offer support or gently guide the session.

They believed that the mechanism of action for healing wasn’t drugged up talk-therapy, but the “peak experiences” that people had on psychedelics. Accordingly, the therapeutic team didn’t perform ordinary psychotherapy. Can you imagine talking with a therapist about your mother during the peak of an acid trip? Instead, they offered “emotional support and companionship,” the seed of what would later be formalized as “non-directive” supervision.

In 1968, a Czechoslovakian psychoanalyst named Stanislav Grof joined Spring Grove, serving as Chief of Psychiatric Research for five years. To this day, at 94 years old, Grof remains a Major Player in psychedelic therapy. I have attended conference sessions where people mostly just clap in appreciation of his work for 45 minutes.

At Spring Grove in the early 70’s, Grof developed what was basically a psychedelic spin on the Rogerian style of therapy pioneered in the 1940s. Note that Rogerian, or “person-centered” therapy, has also been called “non-directive” therapy.

Spring Grove already embraced the idea that mystical experiences were the mechanism of healing. But Grof developed a therapeutic institution and method around it. As a research fellow named Richard Yensen involved with the Spring Grove work remembers, Grof held “a deeply optimistic view of the intrinsic healing mechanisms released through altered states of consciousness.”

In that view, altered states of consciousness like psychedelic trips, or the Holotropic breathwork Grof would later pioneer, unwound the mind’s resistances and defenses, allowing for an unencumbered expression of the intrinsic healing aspect to do its work. In the same way that your skin “knows” how to heal a cut, your mind knows how to heal trauma, if only you’d get out of its way.

He was not yet using the language of “non-direction,” but his method was the ground from which it would eventually spring.

Despite promising results and favorable media portrayals (like the CBS documentary, LSD: The Spring Grove Experiment), as the political tides turned against psychedelics and new regulations made getting approvals for new research extremely difficult, the center’s psychedelic research came to an end. Their last dose was administered in 1977, by a psychologist named Bill Richards.

IV. In which Spring Grove alumni spread its method to modern behemoths

Richards had joined the Spring Grove team after finishing graduate degrees in both psychology and divinity in the late 60s, where he stayed until that last dose in ‘77. With psychedelic science out of the picture, Richards practiced psychotherapy out of his Baltimore home, patiently waiting to see if circumstances might change and he could work with psychedelics again.

And they did. Richards met Roland Griffiths in 1998, who was assembling a team to run psychedelic research at Johns Hopkins. Richards joined, importing the Spring Grove method to the Hopkins squad, even down to the Hubbard Room decor: “When I designed the space at Hopkins,” Richards told anthropologist Tehseen Noorani, “I purchased similar furnishings.”

The Hopkins team would go on to reignite contemporary psychedelic research, with their guidelines and methodology serving as a blueprint for academic teams from North America to Australia.

Parallel to the academic revival, Rick Doblin and the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies had been scheming for a psychedelic revival since 1986. Their goal was to win FDA approval for MDMA therapy, which, they continue to hope, will kick off a broader cultural renaissance in the acceptance of psychedelics.

MAPS has since become one of the most visible and consequential organizations across psychedelia. Their study designs and therapy protocols have influenced how the rest of the field, from researchers to practicing therapists, approach their own work. And the entire MAPS philosophy and protocol, it so happens, was built around the work of Stanislav Grof and “non-directive” therapy.

Beginning in 2015, the MAPS treatment manual that both enshrines and propagates their model adopted the label of a “non-directive approach” as the sixth core element of their therapeutic method:

A nondirective approach to therapy based on empathetic rapport and empathetic presence should be used to support the participant’s own unfolding experience and the body’s own healing process. A non-directive approach emphasizes invitation rather than direction.

So we now have a direct lineage of the Western Model running from Al Hubbard, to Spring Grove, to Hopkins and MAPS, and through them, across today’s academic research and psychedelic therapy protocols.

The story, of course, goes on.

V. In which States adapt the clinical model for general adult-use

Most of us do not trip via clinical trials or psychedelic therapy, underground or otherwise. These are small, though visible and consequential, slices of how psychedelics are actually used by people in general.

But if you are of the belief that psychedelics should be generally accessible to anyone who wants them (maybe with varying degrees of screens, supports, or restrictions), then we need more legal access points than just medical prescriptions and participants in academic research.

So thought two Oregon-based therapists, husband and wife Tom and Sheri Eckert. With momentum growing from the clinical research, they wanted to break the medical industry’s monopoly over the legal psychedelic supply. So they wrote what would pass in 2020 as Oregon’s Measure 109, a bill that legalized a “supported adult-use” model and set up the first state-sanctioned psychedelic program for any interested adult.

In practice, that means no longer requiring a diagnosis or prescription to gain access to legal psychedelic use. All you need is a few thousand bucks, and to live within traveling distance of Oregon.

Measure 109 established a state regulatory agency — the Oregon Health Authority — to setup a licensing process for both service centers and facilitators. Beginning in 2023, these psilocybin service centers began accepting customers. Although there’s some variation, the bones of the structure are familiar: clients do preparatory sessions with their facilitator beforehand, and generally trip alone1 inside of a comfortable room while under the non-directive supervision of their guide.

In Oregon’s model, non-direction is a requirement. As per the third item of the facilitator conduct guidelines from the Oregon Health Authority:

A facilitator must use a nondirective facilitation approach to providing psilocybin services to clients during preparation, administration and integration sessions.

A couple years later, Colorado followed suit, passing their Natural Medicine Program, legalizing more or less the same thing, but without the same codification of non-direction.

Facilitators still learn non-directive methods in their training curriculum. But the absence of a mandate stating that all facilitation must be non-directive opens the door for clients to opt-in to guides who offer things like guided meditations, or work with specific cosmologies that interpret psychedelic experience in particular ways2.

The loosening grip of non-direction over legal psychedelia, together with the rising interest in group modalities, suggests that the hegemony of the Western Model is already coming apart. That means the question is not really one of revolution; “how do we overthrow the Western Model?” Instead, I’m more interested in exploring something like, “how can we skillfully participate in the ongoing deconstruction of the Western Model such that things work out as well as possible?”

VII. In which we answer the question

So, why do most of our legalized approaches to psychedelics have us all tripping in this one particular way? Alone and left to our own interpretative devices? A rough sketch:

We sanction tripping this way because Al Hubbard promoted comfortable living-room-like settings, because Springfield Hospital couched psychedelic therapy within clinical norms, because Springfield alumni anchored that approach in today’s twin behemoths of academia and healthcare, because states are modeling their programs off of those clinical best practices, and because all of this gels with the Western values of individualism and autonomy, such that what is actually an extremely culturally particular way of ritualizing the psychedelic experience dons the cloak of objectivity, undermining the apparent value of allowing for other ways of tripping.

But nestled into the latter half of that progression is that simultaneous story of undoing.

In the academic and healthcare arenas, the scope of interest (and funding) is expanding from a short list of mental health conditions to a lengthening scroll of research questions. Linguists, anthropologists, and artists are getting involved as the field of psychedelic humanities boots up. Organizations are reviving research into psychedelic-assisted innovation. Clinicians themselves are studying how the narrative framing of the potential psychedelic effects their study teams provide to participants affect experiential outcomes.

The expanding list of research questions is creating friction against the limitations and influences of atomized non-direction.

In the jump from research and clinical practice to general adult-use in Oregon and Colorado, all manners of red tape and bureaucratic constraints were lifted (replaced by others, to be sure, though I think the balance still leans towards more flexibility).

Taking legal psychedelia out of healthcare loosens the standard of non-direction3. Already in the second state program, the mandate of non-direction slipped into more of a suggestion. Exceptions for tripping at home were introduced. More liberalizations will likely follow, and the saga, as always, will roll on.

VIII. In which the pioneers reflect

In 1979, after the first wave of psychedelic research had come and subsequently crashed, the major players of the movement gathered for a reunion at the Los Angeles home of psychiatrist Oscar Janiger. Attendees included Timothy Leary, Aldous Huxley, Alan Watts, Humphry Osmond, Sidney Cohen, and the Captain himself, Al Hubbard.

“The great project to which they devoted their lives lay in ruins,” Pollan writes. But there was no doubt that something had been accomplished. Or, at least, something had transpired, and they had been at its center.

We have a scratchy but audible video tape of the event.

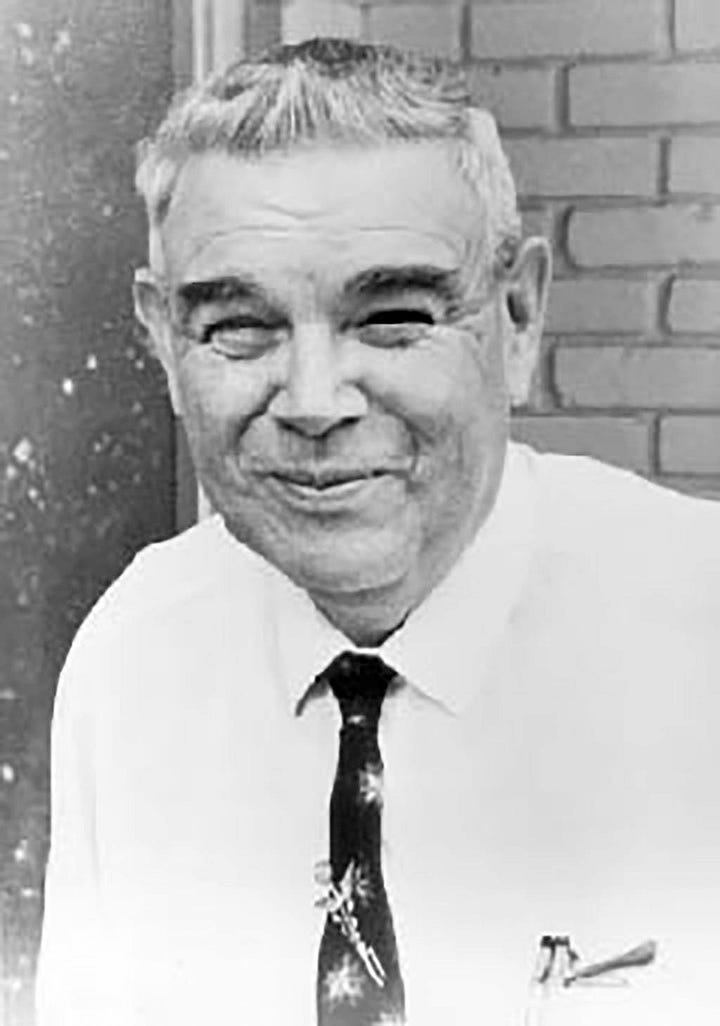

Hubbard, now a plump old man wearing a paramilitary uniform, is sat rather uncomfortably next to the high priest of LSD himself, Timothy Leary. Hubbard was likely still resentful of Leary’s antics, which many felt played a decisive role in the crackdown on LSD.

Someone asks Hubbard when he and Leary met. It was at Harvard, 1961. “I gave him a bottle of about 500 tablets [of LSD],” Hubbard says. “I remember that,” Leary responds. “The galactic center sent you down just at the right moment.”

By then, Hubbard had gone broke. The shutdown of LSD research shuttered his centers, forced him to sell his Vancouver island, and landed him at a trailer park in Arizona. He died in 1981, alone.

Later, a guy on the far end of the couch turns to Hubbard.

“When you started with it all, Al, you had some kind of a purpose or vision in mind, didn’t you?”

“I’ve still got it. I haven’t changed my mind,” Hubbard shoots back.

“And why? What are you doing it for?”

“I think it’s a thing to do…just to keep on waking people up and let them see themselves for what they are.”

The Oregon setup does allow for group trips, through they tend to be a luxury option that puts people up in a nearby house, and shuttles them back and forth from the service centers for their tripping sessions. And during those sessions, everyone’s still following the tripping alone protocol (eye shades, blankets, not interacting with others). It’s more like the group trips alone, together, rather than doing any sort of communal activity or ritual that brings them into contact with each other during their sessions.

A lot of the real innovations around offering directive facilitation in Western contexts are happening in the gray areas of decriminalized, but unlicensed guides. In states like Colorado where psychedelics are decriminalized, professionals can sell “harm reduction coaching” while “gifting” psilocybin mushrooms to clients, allowing them to guide sessions without breaking the law. This allows them to skirt most of the constraints on facilitation regulations.

A non-direction mandate is useful in that it makes it illegal to intentionally use psychedelics to indoctrinate people into your cult. But perhaps you believe in God, or some divine force, and want to work with a psychedelic guide who not only believes in your flavor of divinity, but specializes in ritual practices meant to facilitate a deeper connection with, or exploration of, that divinity. That could take the form of guided meditations, or iconography, or ecstatic dance, or ceremonial hymns and prayers, or any number of rituals with an explicitly directive intent. Informed consent for this sort of thing is tricky business. But it’s worth grappling with.