Mind Matters

The Ecology of Attention, What's the Use of 'Truth'?, & Branding the Self

A few different threads to explore today:

Attention. I find attention one of the most timely, complex, and consequential topics today. It’s an intersection for meditation, philosophy, economics, and just about everything else. Continuing on from last time, we’ll explore how the prevailing narrative of an ‘attention economy’ has a reductive, troubling effect on our understanding of what attention is (as a resource vs. a malleable, experiential interface with life), what it can be, and how it can change our lives.

The latest MusingMind essay, When Truth Doesn’t Work, exploring what we might actually mean, or be looking for, when one claims to be after ‘Truth’, which may just be a proxy for an inchoate desire to change how we experience our lives via our perceptual and attentive interfaces.

When the Self Becomes a Product. Where David Perell suggests that the future (more like unseen present) of media is brands becoming more like people and people becoming more like brands, Anne Peterson’s recent essay took this to a fascinating extreme: growing up in an omnipresent digital media environment transforms the very ‘self’ into a branded product. Life becomes a stage for the never-ending work of optimizing that brand, the self. What could go wrong?

Followed by the brief book review section.

Unwind & enjoy!

The Ecology of Attention

Attention is not merely a resource, Dan Nixon writes, but a “way of being alive to the world.” In Yves Citton’s The Ecology of Attention (reviewed here, and here), he suggests attention is not economic, but ecological. In the same way that Mark James explored habits as more responsive to environmental factors than acts of individual willpower, Citton explores attention not only as a matter of individual concern, but ecologically situated within the larger contexts of media interfaces, political systems, economic institutions, etc.

So yes, meditate, reflect, journal, take psychedelics (carefully), perform whatever individual practice inverts your attention upon itself, but also consider the larger forces at play in shaping attention. The economic giants whose main currency is consumer attention. The social media environment where we solicit the attention of others, communicated via likes. The individual is but one node in a vast ecological web of forces co-creating our attentional interfaces with life. In modern society, attention is not a private experience; attention is an individual experience fashioned by collective forces.

This isn’t inherently bad, it just makes it imperative to ask, and act upon, the kind of attention we’d most like to cultivate.

This is where I don’t feel we’ve explored enough, culturally. A binary, on-or-off view of attention inhibits this line of questioning. Attention-as-resource neglects the dimensionality, and potentialities of the interface itself. If attention serves, as I suspect it might, as the pilot of our first-person experience, as the medium upon which we encounter life, then the possibility of deconstructing and reconstructing attention is nothing less than a reconstruction of how we experience life.

Deconstructing and reconstructing the medium of experience is another way of describing contemplative practice, the varieties of meditation. Fruitful accounts of the benefits to a rich attentional interface abound in what Annie Dillard calls “the literature of illumination”, those timeless humans whose writing we return to for a reminder of what it can feel like to be alive.

By way of example, Dillard’s mentor, Henry Thoreau wrote in his journal:

“If I were confined to a corner of a garret all my days, like a spider, the world would be just as large to me while I had my thoughts about me”

How many of us can say the same? Or consider when William Blake sees the world in a grain of sand, heaven in a wild flower. these objects might as well have been a grain of rice and a wild boar. What mattered was the attentional interface, not the objects being attended to. He would have seen the world, eternity, and heaven in whatever he looked at.

If one buys that attention captains our first-person experience, and is itself a constructed experience (and therefore available for deconstruction), we’re left with the question I’m wading through. What to do about attention?

The problem arises if we wind up valuing a kind of attention other than the mass-produced variety. In a world of growing connectivity, we’re increasingly ‘plugged in’ to the forces acting upon attention. How can you change something that is beyond one’s individual capacity to change? If attention is ecologically situated, and its ecology includes the economic, political, and social landscapes (not to mention genetics, luck, and so on), what can be done?

There are (at least) two threads here. There is always a degree of potential within the space of one’s individual life to operate upon their own experience. These are the increasingly common, almost banal refrains of self-help and thoughtful philosophy alike: meditate, journal, become conscious of your own mental processes, be intentional about as many aspects of your life as possible, etc. Exercise whatever agency and autonomy one finds available.

The second frontier is collective, the ecology of attention beyond the individual. This space is wide open. I don’t know if this space calls for novel forms of regulation, radical decentralization, or what. Still working through Citton to see how he envisions us acting upon attention’s larger ecological forces.

But a third, and perhaps more interesting thread running through these various perspectives on attention was recently articulated by Mark James:

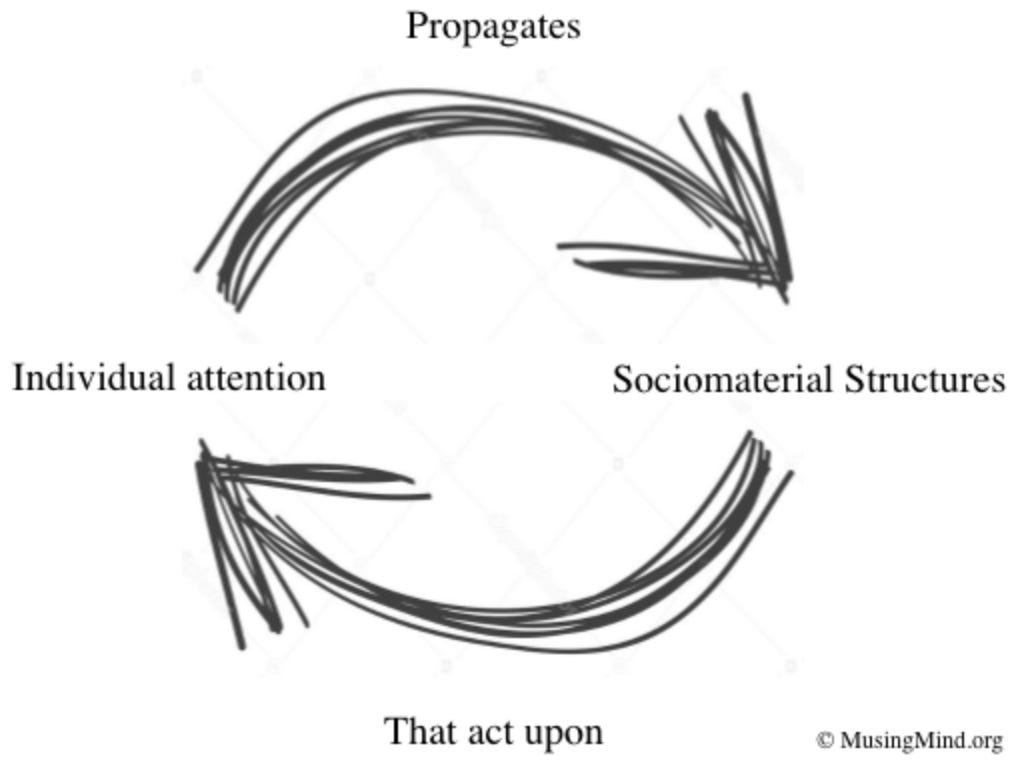

“…the role of individual attention in the propagation and perpetuation of sociomaterial structures”

Which, in turn, affect individual attention, which sustains behaviors that once again propagate and perpetuate sociomaterial structures, in an infinite recursion of attention-constructing loops.

In the coming month I’ll be working more through Yves Citton’s The Ecology of Attention, as well as Jonardon Ganeri’s “Attention, Not Self”, and hope to come up with better ties between the ecological and contemplative perspectives on attention.

New Essay

The pragmatists, led by William James, incited something of a copernican revolution in our understanding of ‘Truth’. Truth is not a stagnant, inherent property in any pithy statement or objective knowledge.

Rather, truth is a functional measure of what works. To find out what it means for something to ‘work’, consider why one desires to find ‘truth’ in the first place. From the essay:

“Desiring ‘truth’ is less a statement about what really exists than a condemnation of my current condition. It’s a recognition of the falsity, or unsatisfactoriness, of the state of mind I inhabit. When looking for truth, I’m really looking to change my mind. To re-engineer and iron out the perceived falsity and unsatisfactoriness of my condition.”

To figure out what works, what improves my condition (or perhaps improves my attentional interface), it becomes vital to develop a clear, discerning view of our own internal happenings, which is essentially vipassana, or insight meditation. Using the cultivated internal view of insight meditation, we can begin the work of recreating our routines, committing to vitalizing practices that give rise to healthier states of mind.

Read the Full Essay Here.

When the Self Becomes a Branded Product

‘Digital natives’, as we now call humans who grow up from infancy in an environment of digital media, are something like a new breed of human being.

No human being has yet lived a full life, from birth until death, in an environment of digital media. It’s like our species stumbled into a new room and hasn’t yet found the lights. I can’t imagine the unrecognizable ways in which the evolving media environment is reshaping human psychology.

In a recent essay, Anne Peterson illuminates at least one of these dark corners I’ve been feeling my way around, as of yet unable to articulate. She writes that omnipresent connectivity to media interfaces, and to the watchful eyes of others, is turning the very selves of digital natives into branded products:

“‘Branding’ is a fitting word for this work, as it underlines what the millennial self becomes: a product…the work of optimizing that brand blurs whatever boundaries remained between work and play. There is no “off the clock” when at all hours you could be documenting your on-brand experiences or tweeting your on-brand observations. The rise of smartphones makes these behaviors frictionless and thus more pervasive, more standardized.”

Smartphones are a central driving force here; they turn every moment into an opportunity for further branding, and every un-advertised instant a missed opportunity.

“Now, your phone is a sophisticated camera, always ready to document every component of your life — in easily manipulated photos, in short video bursts, in constant updates to Instagram Stories — and to facilitate the labor of performing the self for public consumption.”

Her angle is burnout, that existing within such an omnipresently ‘plugged in’ milieu precipitates a debilitating variety of exhaustion.

It’s an interesting angle, but I’m more curious about the evolution of how we experience ourselves in this new, performative environment. Media interfaces become ways through which we both figure out and signal who we are. How might this change the experience of oneself? What new possibilities and perils enter into the mix?

How is the consciousness of a digital native different from the digitally naive?

I’m unversed in media theory, and would love any pointers towards reading on this front (I have McLuhan in mind, but are there any similar figures writing today?).

Brief Book Review

The Anatomy of Melancholy, by Robert Burton

This is one of those books that previous adored-books referenced so many times that I finally had enough, left with no choice but to investigate. I had no clue it would be 1,400 pages.

BUT, with a review like this from The Guardian, I soldiered on, bought the book, and still dip into it sporadically. It’s like a great big ocean of human experience that one can jump into from any angle, in any random location, and enjoy the waters.

“It's not a novel, a tract, an epic poem, a history; it is, quite self-consciously, the book to end all books. Made out of all the books that existed in a 17th-century library, it was compiled in order to explain and account for all human emotion and thought. It is not restricted to melancholy, or, as we call it today, depression; but then a true study of it will have to be - if you have the learning and the stamina - about everything.”

Burton essentially spent his life in a 17th-century library, all of it (his life and the library), and finally got to a point where he actually felt the sheer accumulation of knowledge in his head was bothersome, festering in a kind of abscess that he needed to rid himself of, and so this book is one great big brain-dump of a man who read all there was to read in one of the greatest library’s of the 17th century:

“I first took this task in hand…to ease my mind by writing; for I had a kind of imposthume [abscess] in my head, which I was very desirous to be unladen of, and could imagine no fitter evacuation than this.” (Burton)

His wit & humor first struck me, making all the rest immeasurably more appetizing. I’ve still only read a fraction of it, but even the occasional paragraph taken here or there is delightful, and brimming with erudition.

Find the book on Amazon

~ fin ~

If you’ve made it this far, thanks for reading! I’m experimenting with longer-form newsletters, as a written medium separate from the MusingMind essays, allowing for shorter takes on a wider array of things. I’d like this Mind Matters newsletter to evolve closer towards its mission statement:

The Mind Matters Newsletter chronicles my own becoming as a reader, writer, thinker, and more generally a human confounded, and invigorated, by our inscrutable position in the cosmos.

Not a newsletter full of links leading you elsewhere, but a resting place for the interested reader, full of ideas and invitations into a more examined lifestyle.

In service of all this, feedback is king. Especially if this all bored you, if you’ll unsubscribe from any similarly self-indulgent intrusion upon your inbox, or if something resonated with you; please reach out for any reason, or check out the full website: www.MusingMind.org.

Cheers,

Oshan