Mind Matters

Holy Moments

Mind Matters is a newsletter written by Oshan Jarow, exploring post-neoliberal economic possibilities, contemplative philosophy, consciousness, & some bountiful absurdities of being alive. If you’re reading this but aren’t subscribed, you can join here:

Hello, fellow humans!

Two new things to share, apart from the usual miscellany:

I published a new podcast episode - Consciousness & Fiction with Erik Hoel.

Erik has a (phenomenal) novel coming out in April about a young scientist obsessed with discovering a grand theory of consciousness. We discussed all sorts of themes from his book, plus: the unique way fiction represents consciousness; some theories at the frontier of consciousness research; the relationship between evolution, complexity, emergence, and consciousness; and the limits of what science can tell us about consciousness.New essay: To Annie Dillard’s Astonishment

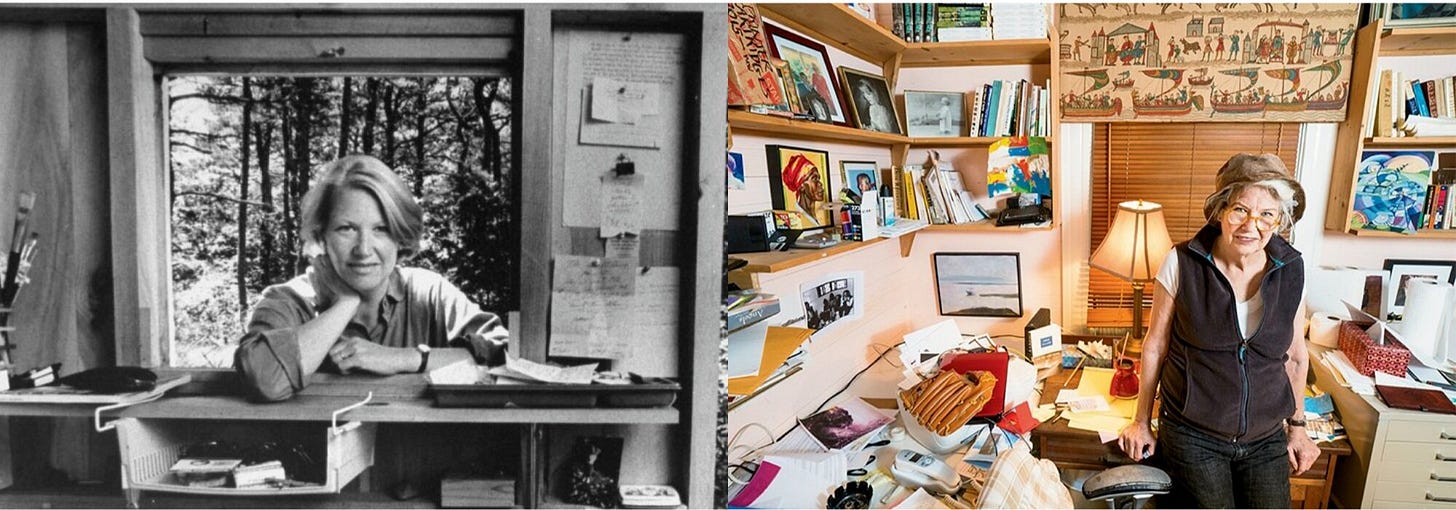

Annie Dillard has long been my favorite writer. I’ve often quoted her on everything from bugs to God, but I’ve always wanted to write up something of an incomplete biography of her life and work. If you’re interested in Annie Dillard but haven’t read her books, I hope this essay might offer a nice overview, a nice dip into the bewildering chambers that her books offer.

Ok, in we go.

Some Preparatory Notes on my Annie Dillard Essay

"Do you suffer what a French paleontologist called 'the distress that makes human wills founder daily under the crushing number of living things and stars'?”

The best way I can think to describe Dillard’s writing is by likening it to a scene from Richard Linklater’s (excellent) movie, Waking Life. In a scene subtitled The Holy Moment, filmmaker Caveh Zahedi is speaking with poet David Jewell about the idea that all moments, seen from enough of a birds-eye, existential perspective, are ‘holy’. But we don’t see every moment as holy, for a number of reasons.

Emerson: “Heaven walks among us ordinarily muffled in such triple or tenfold disguises that the wisest are deceived and no one suspects the days to be gods.”

From an evolutionary perspective, walking around entranced by the holiness of the universe is not a good strategy. Yes, the odds are absolutely impossible that any of us are here at all, and everything is beautiful and striking if you tilt your mind just right. But if you perceived everything this way all the time, you’d be a sitting duck for predators. The brain did not evolve to perceive truth; it evolved to keep us alive. “Fitness beats truth”, as Donald Hoffman says.

Here’s Caveh:

"You know, like this moment, it's holy. But we walk around like it's not holy. We walk around like there's some holy moments and there are all the other moments that are not holy, right, but this moment is holy, right? And if film can let us see that, like frame it so that we see, like, 'Ah, this moment. Holy.' And it's like 'Holy, holy, holy', moment by moment. But, like, who can live that way? Who can go, like, 'Wow, holy'? Because if I were to look at you and just really let you be holy, I don't know, I would, like, stop talking...I'd be open. And then I'd look in your eyes, and I'd cry, and I'd like feel all this stuff and that's like not polite. I mean it would make you feel uncomfortable."

For Caveh, film is a method of ‘framing’ moments so that we can see them as holy. For Annie Dillard, writing is another method of doing the same. For her, it’s the inverse: there’s no time to live any other way. Stand under the waterfall of holiness in all moments, the deluge that makes your knees buckle. Dillard:

"What do we ever know that is higher than that power which, from time to time, seizes our lives, and reveals us startlingly to ourselves as creatures set down here bewildered? Why does death catch us by surprise, and why love? We still and always want waking. We should amass half dressed in long lines like tribesmen and shake gourds at each other, to wake up; instead we watch television and miss the show."

Her books serve a similar function to this imagined scene of lined-up tribesman shaking gourds at each other and yelling “WAKE UP”. She lines up events, one after another, holy moment after holy moment, each with its own muffled cry: “WAKE UP”.

And the aforementioned scene:

Consciousness & Fiction: Erik Hoel

"For what snapping amphibious creature first contained that divine spark? Did it first wink on in the neural nets of swimming hydras or did it slowly accumulate like dust over all biological processes? Was it brought about by predation, by the need for ambulation, avoidance, and planning on the millisecond timescale? Could it have arisen from such dark origins, as biblical as freedom arising only from the Fall? And what of its fate forward in time? What beautiful consciousnesses will one day occupy the tangled bank of our solar system if we can only persevere?" (Hoel, The Revelations)

There are at least three fundamental questions about consciousness:

What is it?

What can it be?

What should it be?

I. What is Consciousness, Integrated Information Theory, Give me More Consciousness

Erik worked with Giulio Tononi on developing Integrated Information Theory (IIT), a leading theory of consciousness that inverts the question. While it’s true that we really have no idea what consciousness is, or why it is, it’s also true that nothing else in the universe is as obvious or familiar to us as the fact that consciousness exists. We know what it’s like, even if we can’t say what it is.

Therefore, IIT takes as its foundational premise that consciousness exists. Given that consciousness exists, IIT then tries to derive from that most familiar experience the necessary conditions for its existence, and map those conditions out in a mathematical structure that I do not understand, but allows scientists to figure out 1. where consciousness is in the world and 2. how much consciousness there is.

This idea of ‘how much consciousness there is’ in any given system, the volume of consciousness, is intoxicating the more you sit with it. One of my gripes with the nueroscientific study of consciousness is that it can’t seem to answer any normative questions about consciousness. Questions of that third category - what should consciousness be? Buddha says consciousness should have as little suffering as possible. States of consciousness laden with suffering are bad. Causing suffering is bad. What can the scientist tell us that helps us figure out how to live, how to direct our own consciousness?

But the volume of consciousness is a sort of sneaky, interesting bridge. You can make an interesting evolutionary case for ‘more consciousness’ as a normative value. In the economic world, a lot of energy has gone into critiquing the ‘more is better’ framework. But in the consciousness world, what if more consciousness is better? It sort of seems like, at least on earth, evolution has been driving in that direction anyway.

II. What Can Consciousness Become?

Thomas Metzinger writes:

“The mathematical theory of neural networks has revealed the an enormous number of possible neuronal configurations in our brains and the vastness of different types of subjective experience. Most of us are completely unaware of the potential and depth of our experiential space. The amount of possible neurophenomenological configurations of an individual human brain…is so large that you can explore only a tiny fraction of them in your lifetime. Nevertheless, your individuality, the uniqueness of your mental life, has much to do with the trajectory through the phenomenal-state-space you choose1.”

William James says the same thing, with a more poetic tint:

“Our normal waking consciousness, rational consciousness as we call it, is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different. We may go through life without suspecting their existence; but apply the requisite stimulus, and at a touch they are there in all their completeness, definite types of mentality which probably somewhere have their field of application and adaptation. No account of the universe in its totality can be final which leaves these other forms of consciousness quite disregarded. How to regard them is the question — for they are so discontinuous with ordinary consciousness. Yet they may determine attitudes though they cannot furnish formulas, and open a region though they fail to give a map. At any rate, they forbid a premature closing of our accounts with reality.”

During my conversation with Erik, I tried (yet again) to convince him of the value in becoming a Buddhist monk and doing lots of acid. The point isn’t to ‘explain consciousness’, I nagged him with, but ‘to change consciousness’, as Alan Watts & co. have burned into my brain.

I liked his rebuttal, but I’m still mostly interested in what I can know, or what science can learn about consciousness insofar as it furthers our capacity to explore and change its phenomenological qualities - what it feels like.

Erik:

“What I think a novel does is that it can give you some of that experience. Frankly, the goal of the book is to be like, okay, so this is what it's like to be Kierk. The point is to convey what it is likeness. And the interesting thing is that even with a perfect scientific theory of consciousness, it's unclear that you could ever transmit that, what it is likeness.”

“What it is likeness” is exactly what philosophers refer to as “the hard problem of consciousness”. It’s unclear that science will ever be able to tell us much of anything about “what it is likeness”. I can “know”, everything about consciousness, but until I feel it, or experience what different states of consciousness are like, I’m missing the whole show.

III. What ‘Should’ Consciousness Become?

Thomas Metzinger:

"As soon as we concern ourselves with what a human being is as well as with what a human being ought to become, the central issue can be expressed in a single question: What is a good state of consciousness?"

This is the normative component that enlightenment-style science has largely hollowed out. Of course, science rocks. We should keep doing it as much as possible. But the post-modern deconstruction of meaning tore apart the existing how-to guides that gave us a collective sense of how we should live.

Metzinger’s question, and bringing together cognitive science with new philosophies like speculative materialism, can provide some interesting paths forward. A ‘good’ state of consciousness can serve as a new quasi-universal value. Specifically, building the social conditions that support the development of these ‘good states of consciousness’ is a way we can bring together the social sciences with existential philosophy.

Erik & I get into all these sorts of questions. You can find the podcast here:

End.

As always, you can respond directly to this email with thoughts, comment on the Substack version of this post for public discussion, or reach out on Twitter. You can find more essays & podcasts on my website. I’m here for conversation & community.

Until next time,

Oshan

Of course, as I often holler about in terms of the link between economics and consciousness, we don’t entirely choose our configurations of consciousness, so much as have them imposed upon us by the socioeconomic environments that frame our lives.