Resonance: a bridge from neuroscience to sociology

Harmonic vibrations are a unifying principle that can tie consciousness to capitalism.

Hi, I’m Oshan. This newsletter explores topics around emancipatory social science, consciousness studies, & together, the worlds they may conjure. If you’re reading this but aren’t subscribed, you can join here:

I. Scale-invariant patterns are keys to understanding the cosmos, at least a little bit.

When a pattern stubbornly persists across different scales, it’s probably worth noticing. Scale-invariant patterns are like tiny keys to understanding, to some hopefully non-trivial degree, the universe we’re all floating in.

For example, consider mutualistic symbiosis. The rhizobia bacteria lives in legume roots, like the base of a pea plant. The rhizobia draws in Nitrogen from the air, cooks it, and serves it to the pea for dinner — something the pea is unable to do on its own. In return, the plants shelter the bacteria, while providing abundant sugar for them to munch on.

Now, zoom up a level from microorganisms to amphibians and insects. There is a species of narrow-mouthed frog — microhylids — that forms this sort of symbiotic relationship with tarantulas. The frogs receive protection from other predators by staying beneath, or generally near the spiders. Personally, I strive for the opposite. But the spiders will enact revenge on the frogs enemies, attacking, for example, geckos that make attempts on frog eggs under the spider’s protection. The frogs also get leftovers from spider meals. The spiders also benefit. The frogs eat small insects, primarily ants, that ordinarily make a meal of spider eggs, being too small for large spiders to deal with. These ants are to spiders as mice are to elephants.

Up again. Consider the symbiosis between the small Starbucks locations that nest themselves inside larger stores, like Target. Starbucks gets exclusive access to an enclosed group of customers, and Target gets customers who linger longer, spend more, and now go shopping while hopped up on sugar and caffeine, making for more impulsive purchases.

Scale-invariant patterns are little clues strewn about the world, or step-ladders that hoist us up a little higher to see wider vistas of the unknown landscape.

I found one of these patterns recently, one that scales from brain activity to sociology. Perhaps it’s worth holding in our gaze for a moment, seeing what it might open: resonance.

In neuroscience, harmonic resonance1 is gaining ground as an alternative to neuron-centric theories of consciousness. Rather than explaining consciousness by way of all the individual neurons firing like engine pistons, harmonic resonance focuses on how all firing neurons generate electromagnetic fields that synchronize across the brain.

When we speak of “alpha waves” in the brain, or gamma, theta, and so on, we’re talking about a group of neurons all firing predominantly within the alpha frequency of 8 to 13 hertz (some folks, like Susan Pockett, argue that consciousness is not some mysterious or elusive set of processes, but just is the spatial electromagnetic pattern generated by all this activity2). This synchronized activity is a form of resonance across the brain.

Turns out, elsewhere, the German sociologist Hartmut Rosa has developed his own theory of resonance doesn’t just connect different parts of the brain, but connects people to their environments. He calls it a “sociology of our relationship to the world.” The idea, suitable to a German philosopher, has a pretty grand vision. In a world that has lost coherence around what we’re actually trying to achieve at a collective level, what actually makes for a good life (GDP? Subjective life satisfaction? Driving infant mortality to zero? Leisure time?), Rosa says “I want to firmly establish resonance as the normative yardstick for quality of life.”

Here, resonance is a phenomenological dimension of our relationship to the world. What does our connection to the world feel like? Subjects are connected to their environments, the world, the other, through various “axes of resonance,” which extend outwards and latch onto people (friends, loved ones), things (music, landscapes, a smooth tennis forehand), and totalities (how we relate to what exceeds us, religion or art).

Each of us, “in the course of our lives,” he writes, “experience constitutive moments of resonance in which our wire to the world begins to vibrate intensely, in which our relationship to the world begins to breathe.” Resonance is a vibrating connection between subject and environment, whereas alienation is its opposite. A mute relationship between self and world, a limp wire.

A formal definition is a bit lacking without the book’s other 800 pages of context, but to pin it down, Rosa’s resonance is a kind of relationship to the world “in which subject and world are mutually affected and transformed,” where subjects feel both affected by, and able-to-affect, the world around them.

In the end, we’ll see that these two views on resonance are just different scales of the same pattern. We’ll add resonance to the inventory of scale-invariant patterns along symbiosis, two little keys to understanding the universe.

II. Dipping the toe in brain harmonics, or: your brain is a vibrating steel plate that arranges neural activity into patterns, which are themselves, actually, your mind, or consciousness.

Imagine you’re sitting at a big living room table, with a soft afternoon sun spreading pleasant, soft light through big farm windows. On the table is a large steel plate. In the room with you, across the table, is Steven Lehar, who has a PhD in cognitive and neural systems, and a new theory of mind and brain known as harmonic resonance theory.

He sprinkles a bunch of sand on the steel plate, whips out a violin bow made of Pernambuco wood but stained to a deep mahogany, which creates a nice contrast with the tooth-white horsehair drawn from either end of the bow. He begins drawing the bow perpendicularly along the edge of the steel plate, sending a steady stream of vibrations throughout. The sand begins jumping like agitated beans, slowly shifting and rearranging across the plate into patterns. By manipulating the speed and pressure of the bow, he can manipulate the patterns that emerge.

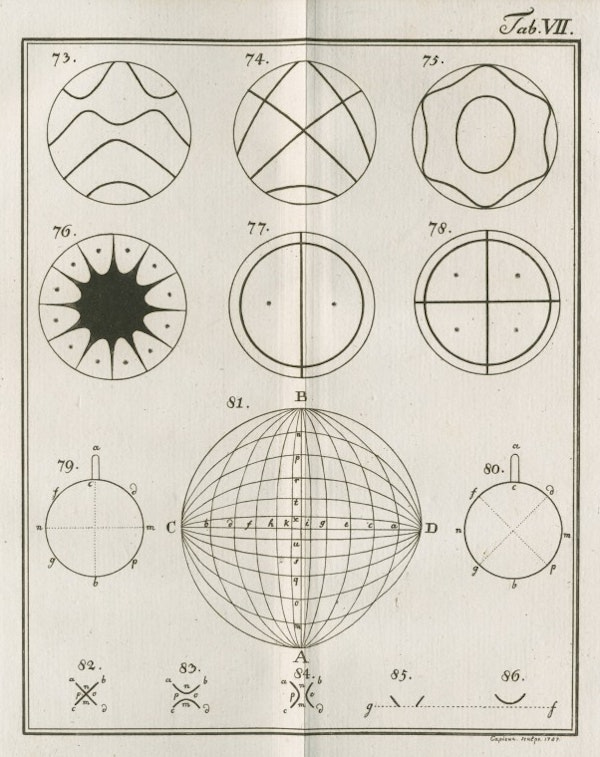

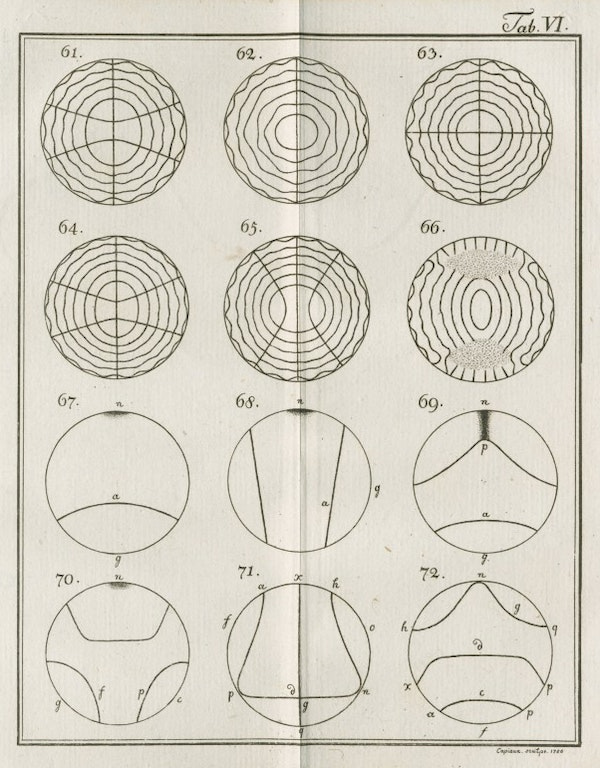

In 1787, the German physicist and musician Ernst Chldani (1756 – 1827), sometimes remembered as the father of acoustics, created a catalogue of these patterns, or the “nodal lines” that are revealed on a vibrating surface.

According to harmonic resonance theory, this is basically how your mind works. Your brain’s electrical activity similarly vibrates (through oscillating neural activity) at various frequencies, which creates electrochemical standing waves in the brain, or electromagnetic patterns set atop the neural substrate, just like the arrangements of sand that emerge on the steel slab.

These waves, writes Lehar, “are proposed as the principle pattern formation mechanism in the brain.” This resolves a few puzzles in the science of consciousness. Most notably, neuroscientists struggle to explain how all the scattered activity in the nervous system gets picked up and integrated into a single, unified moment of experience. This moment, to you, feels like a unitary thing. A gestalt. But if it’s produced by a thousand smaller processes, how are they all woven together?

Lehar:

“The Harmonic Resonance theory finally provides a promising computational principle to account for the unity of the conscious experience, for it is in the very nature of resonances in different resonators to unite when the resonators are coupled, to produce a single coherent coupled oscillation of the system as a whole. The individual oscillators that make up the coupled system have a mutual influence on each other, each one inducing the others to match to its own oscillation, resulting in a single coherent global oscillation state…”

Neural resonance is an integration, a unification of different oscillating processes. And if, as per Pockett, consciousness is the resonating electromagnetic pattern it all gives rise to, well then, there you go. A single unified thing from a bunch of lesser, contributing processes.

Although Lehar’s theory was consistently rejected by the academy, harmonic resonance theory is making its way into peer-reviewed literature. Neuroscientist Selen Atasoy, for example, is on a recent paper:

She uses a method called Connectome Harmonic Decomposition (CHD) to study the relationship between the brain’s structure (the steel plate) and its function (consciousness). CHD, as I sort of understand it, is a way of breaking down the brain’s harmonic patterns and studying consciousness as a distributed pattern of activity across the brain, rather than in terms of “discrete, spatially localized signals.” The paper states:

“The spatially distributed perspective on brain function provided by CHD raises a pressing question: what insights are we missing out on as a field, by limiting ourselves to the spatially-localised view of brain function? The central hypothesis of this work is that the connectome harmonic view of brain activity will provide insights about consciousness that are complementary to the spatially-localised perspective, which has dominated neuroimaging research to date.”

They looked at a spectrum of ‘levels’ of consciousness, from anesthesia-induced unconsciousness, chronic loss of responsiveness from severe brain injury, ordinary consciousness, and psychedelic states. They found a tight relationship between the harmonic patterns of activity and phenomenology in each state.

The measure they use to quantify the brain’s harmonic patterns is a measure of entropy, or “the diversity of the connectome harmonics that are recruited to compose brain activity.”

Next, they plotted each different state of consciousness on an entropy chart, moving from brain-injured (DOC: Disorders Of Consciousness) patients on the left all the way up to tripping on LSD on the right. More ‘active,’ or ‘richer’ states of consciousness tracked with higher levels of entropy, and higher-frequency harmonics:

The objective measures of entropy map well onto the subjective reports of what each of theses states feel like, which is big news. Harmonic resonance begins to build a bridge between subjective and objective, or brain structure and function (consciousness). Just by knowing some details about the formal, objective harmonic patterns, we learn about the subjective experience of what they feel like.

III. A sociology of resonance

Just as brain harmonics propose a relationship between the structure of the brain and the phenomenology of its harmonic patterns, Hartmut Rosa’s sociology of resonance proposes a relationship between the structure of modern capitalist society and the patterns of consciousness that characterize how our relationships to the world feel.

The basic idea is just to extend the same principles of brain harmonics beyond the boundaries of the skull, something that I believe both Lehar and Atasoy would happily grant. Recall that Lehar says “it is in the very nature of resonances in different resonators to unite when the resonators are coupled.” As a vibrational frequency, couldn’t resonances from the brain’s electrical activity couple with resonances from the environment?

For Rosa, not only can this happen, but resonant couplings between the brain and its wider environment are the origins of consciousness, which he sees as relational all the way down. “Human subjectivity and social intersubjectivity basically develop via the establishment of fundamental resonant relationships.”

He cites the German doctor Hans Jürgen Scheurle:

“…processes of synchronized oscillation are the connecting principle of the interaction of brain, body, and environment. Through them, the brain becomes an organ of perception and activation responsive to processes inside and outside the body. It no longer appears as an isolated apparatus, but as the organ of a living being in relation to its world…the function of the brain can only be comprehended in terms of its resonant relationship to its surroundings.”

In both cases, brains and societies, consciousness is the resonant output.

Rosa defines modernity, today’s medium of vibrational resonance, is a society in the mode of “dynamic stabilization,” where continual growth, acceleration, and innovation are required just in order to maintain the status quo.

As a result, “subjects’ positions in the world are constantly shifting and changing, as are those of institutions and organizations,” mirroring the activity of sand on the steel plate, jumping around and settling into patterns. Society itself becomes the vibratory medium, as he describes:

“Resonance requires a vibratory medium; resonant relationships are possible only in mutually accommodating resonant spaces. It is in this sense that I will examine the resonance-facilitating and resonance-inhibiting aspects of the institutions, practices, and modes of socialization constitutive of (late) modern society…we will see how the spheres of work and family, along with those of art, religion, and nature, typically function as modern spaces of resonance, as well as how in particular the pressures of acceleration and competition increasingly serve to block resonance…Every society or social formation is defined by the ways in which it forms and pre-structures how subjects relate to the world…”

You’ll find a related idea in the way Gary Tomlinson describes selective pressures in the context of evolution, citing Deleuze & Guattari’s idea of an abstract machine: “a schema of conditions in which energies and entities meet and fall into a process.” Or the late anthropologist David Graeber’s comment that “structures of relation with others come to be internalized into the very fabric of our being.” Resonant coupling offers a formal, concrete mechanism for these otherwise nebulous ideas.

I’m not going to dive into Rosa’s elaboration on the particular axes of resonance — but I’ll skip to the end, because what he does that’s so refreshing set against the backdrop of most other critical theory is actually propose structural solutions based on his diagnosis.

“So long as the accumulation of capital remains the true subject of modernity’s economic relationship to the world, the imperatives of escalation will remain in effect,” he writes. And escalation — or the dynamic stabilization from above — is, on his diagnosis, a deep resonance inhibitor, causing a social formation that mutes our relationships to the world at scale.

“Growing competition and unrelenting acceleration…promote and favor a mute dispositional relationship to the world, in particular because they allow anxiety to become the dominant form of social being-in-the-world. Stress and anxiety operate even at the neurological level as empathy and resonance killers par excellence.”

How to restructure modernity so as to pre-structure the world, the social formation, in ways that do not inhibit, but foster resonance? He has two main strategies:

Economic democracy: “A more resonant form of modernity’s institutionalized relationship to the world cannot be realized unless we tame, or rather replace, the ‘blind’ machinery of capitalist exploitation with economically democratic institutions capable of tying decisions about the form, means, and goals of production back to the criteria of successful life,” which for Rosa, are resonant relationships to the world. He doesn’t want to abolish all markets, but exempt the vital infrastructure of a decent life from the profit motive, including things like transit authorities, utilities, banks, and health care.

If you’d jive with a slightly less anti-capitalist version of this critique, I think Mariana Mazzucato’s recent paper on “Governing the economics of the common good: from correcting market failures to shaping collective goals” provides a more concrete roadmap for building exactly the kind of economy Rosa means here, but that’s for another newsletter.Guaranteed income: “A basic income could potentially form the bridge between a necessary institutional reform and a change in our cultural mode of existence…it’s appeal lies…in the fact that it could shift the basic mode of being-in-the-world from struggle to security, thus removing existential anxiety from the equation without undermining a positive economic incentive structure.”

I’ve just published a piece over at Vox on how basic income is actually not very radical. But what I really meant was that in macroeconomic terms, basic income wouldn’t be a huge disruption. Implementing any actually viable basic income (which rarely affords more than poverty-line income) wouldn’t do anything crazy to GDP or labor force participation, it’d just create a world with less poverty and higher taxes.

But I think in microeconomic terms, there’s still the potential for, as Rosa says, a bridge towards something more profound, if it’s coupled with other reforms. Eliminating poverty would be no small thing.

“Modernity’s relations of resonance are dysfunctional…Modernity is out of tune,” Rosa concludes, but “another way of being in the world is possible.”

As Lehar tells us, “individual oscillators that make up the coupled system have a mutual influence on each other, each one inducing the others to match its own oscillation.” In other words, resonance is dynamic, always changing. And not only can we, each of us our own oscillating members of a vast network of couplings, induce a change in the system via our own oscillations, but as Rosa argues, we can also, through political mechanisms, alter the vibrational medium that structures all oscillating relationships.

We are the sand on the steel plate, but unlike those tiny little grains, we have the power to change our vibrational mediums. We can move steel, build mountains and canals. We can design — to some degree — the patterns that we settle into. Chldani drew diagrams of all the different acoustic patterns he found. Our catalogue is more difficult to convey in an image, it’s the entire human inventory of conscious states, and it is certain that we haven’t even begun to map out all the possibilities.

III. Bridges between resonance scales

A few similarities and speculative bridges between the two modes of resonance described above.

High levels of neural entropy may be the signature of vibrating axes of resonance between self and world.

Rosa describes high resonance moments as “vibrating wires” between self and world. They’re experiences of transformation, but they also have an element of elusiveness, because the ‘other’ in the resonant relationship is closed off enough to remain a separate, and in some sense inaccessible, entity.

What if these sociological moments of high resonance are marked by high levels of entropy in the brain?

High entropy conscious states are theorized to feel both rich and unpredictable. The richness could map onto the “vibration” of the axis of resonance between self and world. And the unpredictability tracks with both transformation and elusiveness.

On psychedelics, a prototypically entropic state, the transformative sense is clear. But transformations are only possible in relationship to something that is unknown, or elusive. It’s precisely that which eludes us that can transform us. If you knew the world perfectly well, if you could predict its every move, it would never surprise you. It would never transform you. So the sense of transformation discloses the associated elusiveness.

Neither in the brain nor in the world do you want to maximize resonance all the time.

Neurologist Robin Carhart-Harris’ well-received theory of “the entropic brain” argues that evolution has tuned the brain, particularly the default-mode network, to moderate levels of entropy, always keeping them from getting too high.

Predators on the savannah would lick their lips at the sight of a blissed-out human, immersed in a high-entropy phenomenology and marveling at their surroundings rather than scanning for threats. Too much entropy in our ancestral past likely meant a pretty gruesome death.

Similarly, Rosa does not advocate that we should try to live in states of maximal resonance. “The notion that one’s environment must be made resonant in all of its various manifestations thus is not only misleading and potentially dangerous…but is also conceptually incoherent.”

It’s incoherent because resonance always has aspects of inaccessibility and elusiveness. Since perfect and eternal resonance would be neither inaccessible nor elusive, it would not actually be a mode of resonance.

And there’s a way in which more resonance means more of its opposite, alienation. “Alienation born of indifference and repulsion must first become palpable before resonant relationships to the world can be developed. Capacity for resonance and sensitivity to alienation thus mutually generate and reinforce each other.”

Moreover, resonance does not “arise simply from the absence of alienation.” There is no resonance without alienation. “At the root of resonant experience lies the shout of the unreconciled and the pain of the alienated.”

The single-minded pursuit of resonance in all aspects of our lives, on Rosa’s account, would leave us in a similar position to our maximally entropic ancestors on the savannah: toast.

IV.

Each of these modes of resonance — in the brain, in the structure of late modernity — are big and messy ideas. I haven’t managed to do either of them justice, let alone the bridges between them. It’s a work in progress.

But I hope I’ve done enough to spark a similar suspicion in you, that perhaps there’s something worth understanding and elaborating here. If resonance is on the right track, there’s a lot to do — theories to (re)construct, technologies to build, institutions to remodel, policies to draft, maybe some manifestos to write.

If resonance is a tiny key to understanding something about just what the heck is going on here, we should get busy searching the landscape for all the locks we might try and turn. All the secrets we may yet discover, all the suffering we might avert, all the joy we might find, and bask in their warm lights like a campfire discovered somewhere in a dark forest, and when it burns down to a soft and dying ember, as all fires do, off we go again, back into the dark to find the next waypoint. Because there is no resonance that lasts forever — all resonances fade back into whatever they rang out from. Then again they arise, elsewhere, in a shifted key, carrying new and enchanting harmonies, birthing fleeting pockets of salvation that each, at their best and in their own ways, make this whole business of living and dying a little more beautiful, so long as it lasts.

As far as I can tell, Steven Lehar’s version is the most comprehensive, though it has had a rocky relationship with established neuroscience, which may make it sound better or worse depending on your constitution.

Here’s a great introduction to her work if you’re interested.

In addition to restricting the quantity of resonance, I think that our society greatly restricts the modes of resonance. I was recently listening to one of Vervaeke’s podcasts and they were talking about some of the different ways we traditionally used language based on context (family vs. sacred vs. trade) and how as society developed and trade language came to dominate, we have come to use trade language for familial and sacred settings as well as trade. This restriction of modes of resonance limits our capacity to optimize various resonant spaces. It’s like we’re trying to play Beethoven’s 9th symphony but everyone’s playing French horns. For that matter, language itself is only one way that we can resonate with ourselves and our environment. As a meditator and psyychonaut, I’m sure you would agree. But western capitalist culture has little time for such things outside of their potential ability to increase ‘productive’ resonances within a very defined space (mindfulness can increase focus and lower your blood pressure which creates more productive and less costly labor). The medicalization of psychedelics is another fine example. Allow LSD to resonate, but only along very specific wavelengths. Bowing a metal plate is cool, but put the bow to a violin and you can really open up the resonant potentials!

This reminded me of the General Resonance Theory of consciousness. Resonance is definitely happening at multiple scales in our universe. Great analysis