Mind Matters is a newsletter written by Oshan Jarow, exploring post-neoliberal economic possibilities, contemplative philosophy, consciousness, & some bountiful absurdities of being alive. If you’re reading this but aren’t subscribed, you can join here:

Hello, fellow humans.

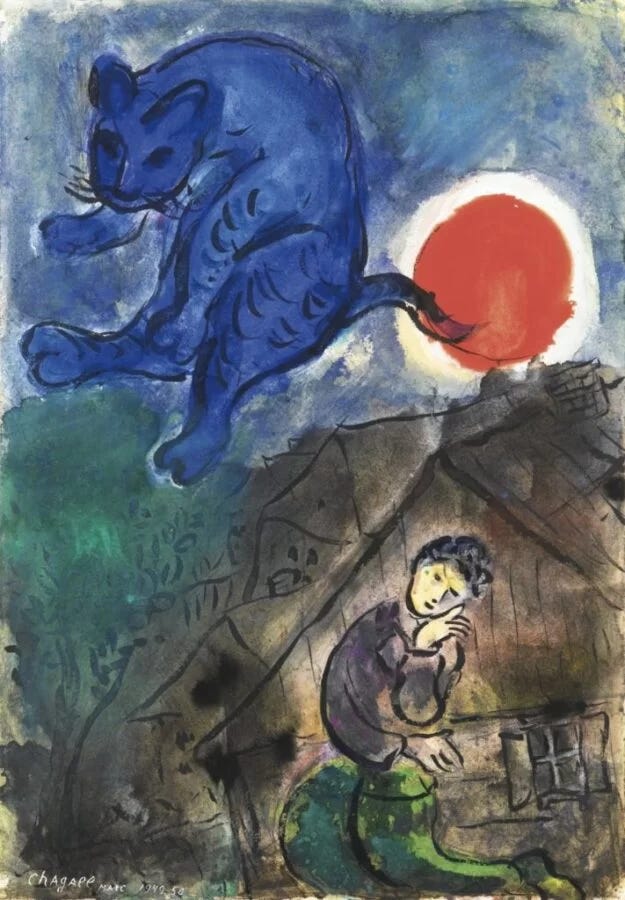

Recently, I found myself staring at my cat as she slept in a triangle of sunlight, wondering whether I’d like to trade my existence for hers. Would I prefer to exist as a creature less sentient? Would swapping the human phenomenology for that of a cat, or, I don’t know, a scallop, be something of a relief?

Maybe this question isn’t just a private trifle, but a framework for understanding what ‘progress’ actually is, in its most relevant-to-us sense?

…

Progress (of What?)

There’s been much talk about ‘progress’ recently. A new (& seemingly wonderful) think-tank has even sprung up in its name, the “Institute for Progress”. But as someone once put it to me, there’s a conspicuous, even gaping lack of '“phenomenological urgency” here.

So here’s a phenomenologically-oriented way to think about what progress is.

The purpose of this long project we call society, the arc of its evolution, should be to progressively bias us towards a sense that we’d rather not trade places with a snoozing cat. Progress should make downgrading the complexity of consciousness an increasingly large bummer. Progress is to make the intensity and depth of human consciousness increasingly desirable, tantalizing, and inviting. To make this unbidden experience something we’re evermore curious about, encouraged by, and if you’ll allow me an excess, in love with.

…

Conversely, this framework can furnish a biting critique of modernity. What if, despite all our advances, the balance of answers to the question of whether or not a human would prefer swapping consciousness’ with a less-sentient creature remains mostly unchanged? What if, in general, we’re no less likely to prefer a less sentient phenomenology?

To be clear, I wouldn’t jump at the chance to swap minds with a Medieval citizen. I wouldn’t relish the opportunity to warp back to a time before bidets, let alone indoor plumbing and penicillin. But I’m not sure this is because we’ve made any significant advances in the phenomenology of what it’s like to exist.

Instead, maybe I cling to these modern comforts exactly because they make that same old interiority, that unchanged sense of what it’s like to exist, more tolerable. I worry it’s dangerous to conflate making suffering more tolerable with alleviating that suffering. The hallmarks of progress would then be recast as compensation, as hush-money for our broader failure to nourish the thing-in-itself, that which is nearest and most intimate in our lives, that which matters most: consciousness.

Here’s André Gorz on how we’ve merely created more comfortable chains, concealing how they tighten:

“In fact, history was both to confirm and invalidate Max Weber's prophecy: the weight of bureaucracy has…become more and more dehumanizing, and the 'shell of bondage' has become at the same time increasingly constraining and increasingly comfortable.”

But, he goes on. The bureaucratic system has reached a crisis point, and in crisis, there is opportunity:

“But, for precisely that reason, the system has reached a crisis point: the operation of the bureaucratic-industrial megamachine and the need to motivate its 'fellahs' to function as cogs, have confronted it with problems of regulation that are increasingly difficult to solve. No rationality and no totalizing view or vision have been able to provide it with an overall meaning, cohesion and directing goal.”

This brings us back to progress. What is “the point” of all *this* (gesturing vaguely at everything)? What is the directing goal of modernity? “Growth” alone is crumbling as a satisfactory answer. In fact, in many respects, understanding progress as growth alone is precisely what landed us in crisis.

The Progress Institute writes that they’re “dedicated to accelerating scientific, technological, and industrial progress while safeguarding humanity’s future.”

That’s great, and I hope 1,000 projects bloom in the same vein. But they’ve made explicit what was previously implicit in the progress discourse: progress, here, is understood as a scientific, technological, and industrial phenomenon.

This way of thinking is perhaps most directly embodied in Marc Andreessen’s “It’s Time to Build” essay, which drummed up much conversation. But as Isaac Wilks responded: “all monuments worth building are monuments to something”, and if our impulse to build lacks that something, it won’t do us any good. We should build, yes, but to what? For what?

One of the most discomforting teachings of the past few hundred years may be that better phenomenology doesn’t simply follow better technology. Economic growth is not a singular road to richer conscious experience.

We have organizations and momentum dedicated to safeguarding humanity’s scientific, technological, and industrial future. Who, then, is dedicated to safeguarding our phenomenological future?

…

Emerson Would Probably Not Switch Places with a Cat

On the note of progress, I was reading Emerson’s journals last night and found this wonderful little metaphor. Though, to be honest, the optimism that we, 200 years later, have failed to follow through on did sting a bit.

“I rejoice that I live when the world is so old. There is the same difference between living with Adam & living with me as in going into a new house unfinished damp & empty, & going into a long occupied house where the time & taste of its inhabitants has accumulated a thousand useful contrivances, has furnished the chambers, stocked the cellars and filled the library. In the new house every comer must do all for himself. In the old mansion there are butlers, cooks, grooms, & valets. In the new house all must work & work with the hands. In the old one there are poets who sing, actors who play & ladies who dress & smile. O ye lovers of the past, judge between my houses. I would not be elsewhere than I am.”

For Emerson, progress is the march of time by which a collective does the work. A group - call it a society - moves into an unfurnished, new house (not unlike we did with America, though we violently ousted the prior tenants), and progressively transforms it from an environment demanding of exhaustive labor, to one that supports playful creativity.

Emerson’s two pictures, of the new house where all must work with the hands, and the old, where all sing and play and smile1, bring us back to my original question: would you trade places?

In 1826, Emerson’s position was clear. “I would not be elsewhere than I am.” Today, 2022, I’m no longer sure this rings true for a larger portion of the population than it did in his day. Any robust & worthwhile commitment to progress will have to contend with this.

Again, with a twist: how might we dedicate ourselves to safeguarding, nourishing, and expanding our phenomenological future?

You can find more writing, podcasts, or even explore my research garden, on my website. If you’d like to talk, reach out! You can reply directly, find me on Twitter, or join the Discord.

Until next time,

~ Oshan

There’s a lot to quibble with in Emerson’s ideas here. There’s a bias against manual labor which we often find in intellectuals (see: Keynes). There’s the idea that a house having butlers and valet indicates progress, rather than exploitation & profusion of low-wage, shitty jobs. But I hope you’ll join me in seeing through these, for the time being.