Contemplative social science: from practice to policy

Society programs your mind well before meditation or psychedelics can re-program it.

Hi, I’m Oshan. This newsletter explores topics around emancipatory social science, consciousness studies, & together, the worlds they may conjure. If you missed it, the last dispatch was on psychedelics beyond psychiatry. If you’re reading this but aren’t subscribed, you can join here:

I.

Psychedelics are the most reliable pathway towards experiencing big, unusual insights into the nature of consciousness I’m aware of. These can be quite jarring, like that feeling of invigoration that surges through your bones after plunging into your first ice-bath, conferring the realization that up to that point, you’d spent your entire life in the lukewarm waters of a default mode of consciousness pre-selected for you by your circumstances, in the same way that a mother might lay out her young child’s outfit before the first day of school.

But the philosopher of all-things-consciousness has a handy word of caution about psychedelics: “When you get the message, hang up the phone.” He continues:

“For psychedelic drugs are simply instruments, like microscopes, telescopes, and telephones. The biologist does not sit with eye permanently glued to the microscope; he goes away and works on what he has seen.”1

On this point, psychedelics are swallowed up into the wider world of contemplative practices, including everything from meditation and breathwork to neurotechnologies and drugs. This entire contemplative proposition is vulnerable to the same temptation, which I’ll call contemplative atomization: collapsing the project of reprogramming consciousness for the better from social structures onto atomized individuals. Contemplative science and its project of positively transforming consciousness should reach all the way out to the largest relevant governing bodies, say, nation-states.

II.

There is a lot of action around the space of contemplative technologies, especially as they fit nicely into the secular-friendly model of spirituality emerging from the cognitive sciences.

The psychedelic renaissance is driving a renewed interest in chemical alterations of consciousness towards more enduringly pleasant, adaptable, and richer states of consciousness that can be made available to mostly anyone who’ll have them.

Scientists are studying advanced meditation in the lab, charting secular roadmaps into “well-documented grades of zest ranging from mild buzzing and passing showers of joy all the way up to almost unbearably strong ecstasies,” as Malcolm J. Wright and colleagues described the meditative states known as the jhanas.

Shinzen Young and Jay Sanguinetti are building an ultrasonic stimulation protocol that may just zap brains in all the right ways to make these deep states of consciousness more accessible to the masses.

But notice the common thread running through them all. There’s you, bestowed with a configuration of consciousness that could do with some alteration. And there are these practices and technologies, that you, the individual, can undertake to achieve whatever new contortion of consciousness you’re hoping for.

If contemplative practice can be understood as reprogramming the mind, too little attention is paid to the “re-”. How is it programmed in the first place? Can we intervene at that earlier stage, so that less work needs to be done when, or if, one gets around to the various mind-acrobatics involved in reprogramming consciousness?

Or: one way to transform consciousness for the better is to follow a regime of contemplative practice that promises just that. Another is to change the conditions that generate consciousness in the first place, so that less contemplative practice is needed. This also has the added benefit of reaching way more people. Contemplative science should focus on both, not just the former.

The conditions that generate consciousness are obviously many, but we can squint at two: genetics and circumstance, the old nature and nurture. Genetic engineering is not my realm, though there’s probably going to be a growing conversation around it for greater baselines of well-being in the coming decades (maybe look to David Pearce for that).

“Circumstances” are also a wide bucket, but contained within: the great leviathan of society, and all its interlocking institutions. So we can ask: how can we reweave the social conditions that give rise to consciousness such that the default states of consciousness humans arrive edge towards higher and higher gradients of baseline well-being?

III.

You probably know the Serenity Prayer:

God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.

When it comes to the transformation of consciousness, contemplative atomization restricts the scope of what one feels they can change to the realms of individual or group practices. But we can change the social structures that determine much of the early environments where consciousness develops in the first place.

Let’s take an example: the expanded child tax credit (CTC). For the duration of 2021, President Biden transformed the CTC from a comparatively mild end-of-year tax credit for working-poor families, to a historic anti-poverty achievement, paid out as monthly checks to every poor American child’s guardian, whether or not they were employed.

Over the course of the year, child poverty was cut nearly in half, with most of the heavy lifting thanks to the expanded CTC. Conservatives worried that an unconditional payment that included unemployed Americans would discourage work, leading politicians to a stalemate (despite the abundance of evidence that the expanded CTC did not, in fact, discourage work). They couldn’t strike a deal, and the CTC reverted back to its prior form at the end of the 2021, leading 2.7 million children back into poverty.

For recipients of the expanded CTC, that was a full year where economic precarity — on measurable dimensions like financial hardship and food insecurity, in addition to regular old poverty rates — played a lesser part in their lives. Economic insecurity and precarity, I would argue, are prime examples of important social parameters we can tune up or down in ways that affect the baselines of consciousness that emerge through the social matrix.

So thanks to one policy, 2.7 million children enjoyed a year of cognitive development with less stress than they otherwise would have. And if that sort of stress exerts a negative influence on the development of consciousness, that’s a dazzling contemplative outcome, achieved at scale.

“There is increasingly strong evidence for the idea that chronic elevation of stress hormones has downstream effects on the neural architecture of the brain’s cognitive and emotional circuits…the implications of the research are very clear: When it comes to mental health, the best treatment for the biological conditions underlying many symptoms might be ensuring that more people can live less stressful lives.”

For every one of the 2.7 million children, there was a family or guardian, too, that enjoyed a temporary reprieve from what the big kahuna in consciousness science Thomas Metzinger would call functionally rigid categories of conscious experience, leading to greater mental autonomy in steering the direction of their own minds.

It’s overwhelming how many other examples suggest that social constructions have been evolving in ways that degrade the default formations of consciousness. The turn from beautiful to cost-efficient-but-horrendous architecture; the jettisoning of public spaces that fostered social connection from urban environments; the for-profitization of our media environments whose engagement and ad-based business models thrive on polarization and shallow interactions; the desecration of our soil, monocrop culture/yield maximization and the subsequent hollowing out of food’s nutritional value, compounded by a deeply confused and financially conflicted nutrition science/industry with subsidies for ingredients that corrode us from within2.

A framework that elucidates the ties between the social and mental architecture could help us, at least, begin to see what we are doing to ourselves.

IV.

Economic policies can achieve contemplative outcomes at a scale that more targeted practices like meditation, psychedelics, or even neurotechnologies probably won’t. But there’s surely a tradeoff.

What the contemplative project gains in scale via policy it loses in the precision and potency of individually-targeted practice. For example, you can pretty reliably design a psychedelic therapy session that will lead to measurably beneficial outcomes in well-being. I expect that very soon, we’ll be able to pair specific meditation programs with their associated neurotechnology-aides (a brain-zapping headset, neurofeedback machine, harmonic resonance recalibrator, whatever) to provide a personally-tailored meditation program that can also reliably induce measurable benefits on short timelines.

I suspect the impact of reducing stress by means of economic policy on baselines of well-being may be somewhat less reliable, and probably lower in magnitude than targeted contemplative interventions. Though I think this has its own virtue: it provides for more diversity in outcomes, which is good.

Contemplatives should not have the final say on what a good life is. Empowering people to adopt their own values free from the influence of economic necessity doesn’t guarantee a Buddhist society, but it does mean that people will be increasingly free to adopt and express their own preferences, rather than being forced into the contemplative idea of a good life.

Scaling up contemplative systems is thus a somewhat lossy process, though you may gain some diversity for what you lose in potency. It would be nice to live in a world where every single human being has a well-resourced contemplative toolkit tailor-made for their particular circumstances and values, but alas. We don’t yet have this sort of abundance. Instead, we can build social systems that have maximally-feasible conditions for the reliable generation of higher and higher gradients of baseline well-being. This idea leans into a sort of contemplative social science (the heart of which is what I explored in this podcast conversation with the economist Christian Arnsperger).

V.

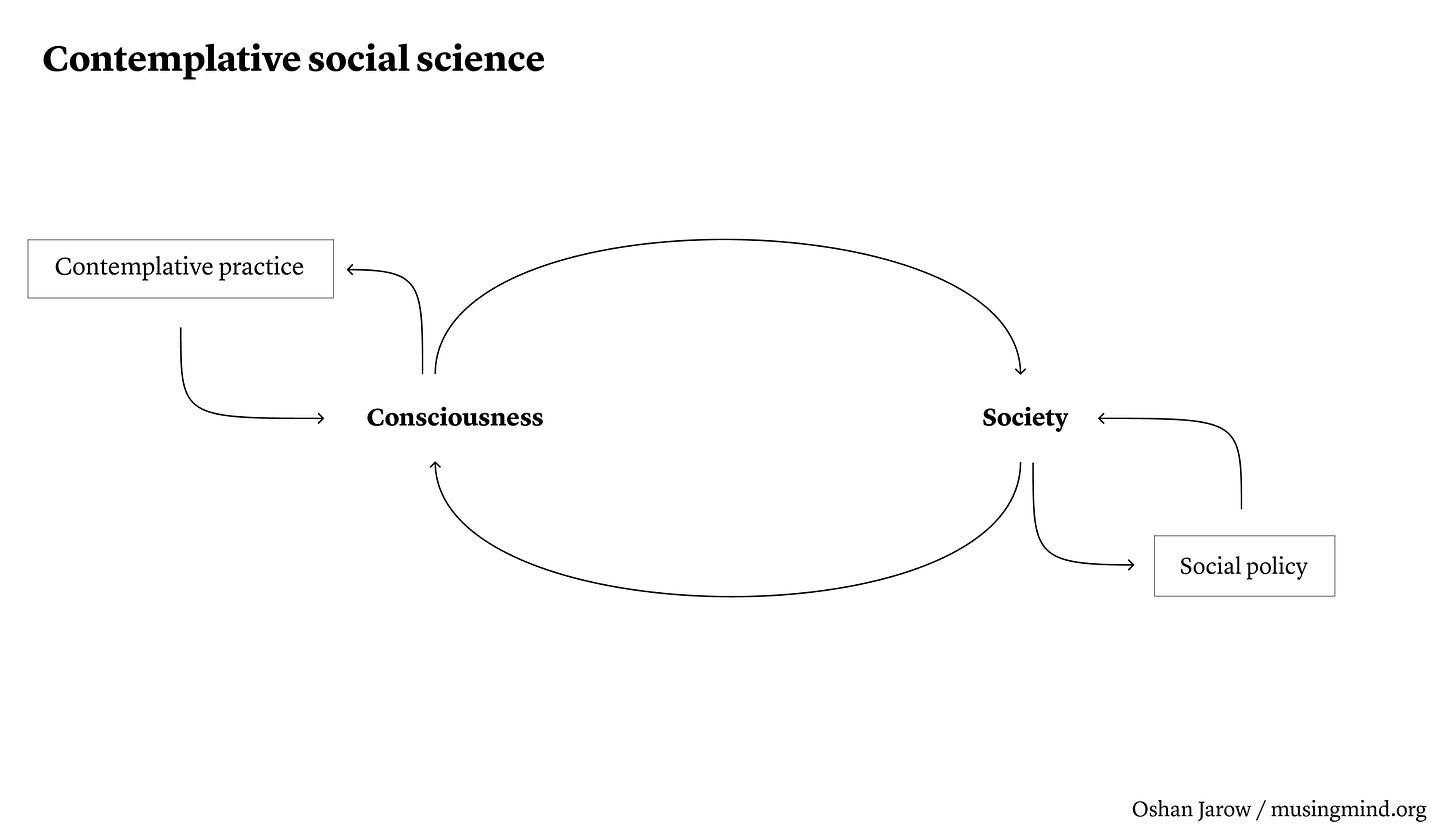

A diagram. Consciousness and social structure are tangled in a reciprocal feedback loop:

Contemplative atomization approaches the transformation of consciousness from one end only:

Contemplative social science adds on the policy dimension3:

We could have some fun with this, imagining connections running direct between social policy and contemplative practice:

VI.

I’m not exactly sure what this all means, in practice. Developing a really detailed & rigorous theoretical analysis of the relationship between social structure and consciousness doesn’t seem all that impactful — I love the Frankfurt School, but their heady analyses of how the structure of capitalism affected the structure of people’s minds preceded neoliberalism, not some wonderful paradigm of emancipatory social science.

Neither do I think advocating for economic policies on the grounds of rigorous contemplative science is a promising theory of change — that’s destined to be niche, and won’t be the platform that gets Joe Manchin to change his mind about making the expanded CTC permanent, or even new and aligned politicians elected (we’re thinking a lot about what makes policy research most useful & impactful over at LEP).

But on this question, I’ll keep digging. I suspect there’s fruitful cross-pollination to be had between the social and contemplative sciences. Each bears a sort of hole shaped like the other.

Social science can’t really say what progress is for. “Shared prosperity,” “human flourishing,” these are upsettingly vague, which is why both Left and Right can agree on them in theory, but agree on little else in practice. Contemplative science can provide a concrete understanding of the real stuff of progress, but it lacks the means of making that happen at scale. I could imagine a sort of contemplative social science, where each completes the other.

But as of now, that idea remains in the penumbrae of my imagination, dimly lit but suggestive enough to keep the hunt alive. This newsletter stalks the prospect in the same vein that the unrivaled author Annie Dillard follows her own subject (which, as far as I can tell, is an unyielding state of bamboozlement at the world we awaken to):

“I am an explorer, then, and I am also a stalker, or the instrument of the hunt itself. Certain Indians used to carve long grooves along the wooden shafts of their arrows. They called the grooves “lightning marks,” because they resembled the curved fissure lightning slices down the trunks of trees. The function of lightning marks is this: if the arrow fails to kill the game, blood from a deep wound will channel along the lightning mark, streak down the arrow shaft, and spatter to the ground, laying a trail dripped on broad-leaves, on stones, that the barefoot and trembling archer can follow into whatever deep or rare wilderness it leads. I am the arrow shaft, carved along my length by unexpected lights and gashes from the very sky, and this book [or in my case, newsletter] is the straying trail of blood.”

But Dillard had no interest in politics. When it comes to the question of what we should actually do, as a collective, she had this to say:

“We should amass half dressed in long lines like tribesmen and shake gourds at each other, to wake up; instead we watch television and miss the show."

If contemplative social science’s study of consciousness is to amount to anything more than fluff, if it is to scale up its hopes for the organized diminution of suffering for all sentient life, it will have to bring itself to bear on the most profane, bureaucratic, and tedious of modernity’s underpinnings: the tax code.

Imagine it: hordes of meditators taking to the streets, psychonauts writing blog posts and academic articles, creators producing Youtube videos, online communities hosting salons, all around a shared objective: reinstate the expanded CTC, for consciousness’ sake.

From the prologue of the revised first edition to The Joyous Cosmology: Adventures in the Chemistry of Consciousness, and upsettingly removed from subsequent editions.

Side note, I would love to help create a website with a full/living inventory of exactly these relationships. A web that shows the cognitive consequences of developments in our social architecture. If anyone’s into this, or knows of already existing projects in the same vein, reach out.

These diagrams are quick & shoddy. If anyone comes up with a more robust depiction, feel free to send my way. I’ll gather them and share in a later newsletter.