On cessations of consciousness & poverty

A very strange meditation skill caught in the lab, & poverty as a damned & damnable location in this system of our making & ever-re-making

Hi, I’m Oshan. This newsletter explores topics around emancipatory social science, consciousness studies, & together, the worlds they might conjure. If you missed it, the last dispatch was on “a general theory of spirituality.” If you’re reading this but aren’t subscribed, you can join here:

Hello, fellow humans.

Today, some notes on catching a strange advanced meditative state in the lab, and rethinking poverty. But first.

Since my last dispatch, we’ve finally launched the full version of the Library of Economic Possibility. This will get a newsletter of its own, but for now, feel free to check that out if you’re interested in the world of policies to actually design a better social structure, or general knowledge-management. There’s a bit of a user’s guide in our launch announcement.

I released a new episode of the Musing Mind Podcast. I got to speak with the sociologist Eran Fisher about algorithms, subjectivity, and both their threats and prospects for emancipation.

Ok, in we go.

Meditation lore is full of stories that mere Western mortals may find unbelievable. But sometimes we get a delightful bone to throw our skepticism: we find someone able to enter strange, advanced meditative states on command, and willing to do so while enmeshed in a host of neuroscience gizmos.

Here is one such instance. A few weeks ago, researchers published a paper attempting to build a conceptual framework for preliminary data that weaves between ancient Buddhist philosophy and modern cognitive neuroscience. They’re trying to make sense of something very, very strange: nirodha samāpatti, or “cessation attainment.”

From a couple thousand years ago, the Mahāvedalla Sutta tells us that one disciple of the buddha asked another, more experienced disciple:

“What’s the difference between someone who has passed away and a mendicant who has attained the cessation of perception and feeling?”

The disciple answers:

“When someone dies, their physical, verbal, and mental processes have ceased and stilled; their vitality is spent; their warmth is dissipated; and their faculties have disintegrated. When a mendicant has attained the cessation of perception and feeling, their physical, verbal, and mental processes have ceased and stilled. But their vitality is not spent; their warmth is not dissipated; and their faculties are very clear. That’s the difference between someone who has passed away and a mendicant who has attained the cessation of perception and feeling.”

The claim here is, again, pretty strange: advanced meditators can attain a state — cessation — where all perception, feeling, and mental processes have stopped. This sounds like death, but it isn’t. Their vitality is not spent. Instead, it’s more like going under general anesthesia. Consciousness switches off, extinguishing without a trace. But only temporarily. Meditators capable of doing this are said to predetermine the amount of time. So they may set the intention of entering cessation for 3 days. And for 3 days, all subjective experience will vanish. The body goes rigid, and you can’t shake them awake. Then, 3 days later, consciousness switches back online.

But instead of emerging woozy and disoriented, like anesthesia recipients, meditators emerge crisp, clear, and refreshed. So this claim isn’t even “advanced meditators can replicate the effects of general anesthesia without the drugs,” it’s more like, “advanced meditators can do something even better than general anesthesia: total and temporary cessation of all conscious experience, but it leaves you refreshed instead of woozy.”

In the paper, they describe what it’s like to awaken from a cessation:

A typical description of alterations of consciousness following nirodha [a sort of micro-cessation, whereas adding samāpatti indicates a longer-term version] may include: a sense of increased clarity, less grasping of experience (i.e., de-reification), increased energy and vibrancy, “openness” of mind and emotions, greater mindfulness, increased cognitive flexibility, less self-centeredness, less concern for the past or future, just to name a few.

This is not the fugue of post-anesthesia. How could someone induce the effects of general anesthesia from within, and without any drugs? And why would it be so beneficial?

The guy who the researchers recently found who can do this on command presented as a very nice, unremarkable guy. He spoke of his cessations like a perfectly fine thing, but no more or less fine than the myriad other fine things one might notice. Birds, trees, a quick and disarming smile. It was encouraging that he wasn’t selling his cessation capability like snake oil.

Here’s what they did:

“…we used EEG to examine the neural correlate of nirodha in an adept meditator with over 6000 hours spent in meditation retreats. In this case, what the participant considers nirodha was observed during vipassana/open-monitoring/insight meditation practice…this meditator reported nirodha as a momentary extinction of experience that was followed by profound alterations of consciousness, a sort of ‘reset’ that is characterized by mental clarity. In the study, we employed a neurophenomenological approach where our phenomenologically trained subject systematically evaluated the mental and physiological processes relevant to nirodha as he experienced them, and these evaluations were used to classify and select 37 high-grade nirodha events for subsequent EEG-based analysis.”

Before getting into what they found, let’s slide over to poverty for a second.

Poverty is still a big thing in the US, but also, maybe it shouldn’t be

A new book about poverty by the sociologist Matthew Desmond is making the rounds, inspiring many and pissing others off in apparently equal proportions. I think it’s excellent, despite making a few strange choices that unfortunately give critics a valid bone to pick that ultimately distracts from the larger message that’s a lot less controversial.

Matt Bruenig of People’s Policy Project did a video review of the book, wherein he made a few points that are shifting how I’m thinking about poverty.

Poverty is a location in the system, not a group of people.

On the statistical aggregate, poverty is not a static group composed of the same people year after year. People in poverty frequently get out of poverty, and perhaps fall back in later on over the course of their lifetime.

The point is that talking about “the poor” could actually feed into the very anti-welfare rhetoric that undermines serious anti-poverty efforts. Because “the poor” conjures the image of a fixed group of people. This makes it easier to imagine “the poor” as an unchanging demographic marked by laziness, lethargy, addiction, or whatever other debunked idea one might still hold.

Instead of a fixed group of people, poverty is a fixed location in the system. That means the way to address it may not be through targeting policies towards “the poor,” but paving over the location of poverty altogether.

Poverty is mostly not an issue of low wages1

Also on the statistical aggregate, there seems to be a conflation between low-wage workers and poverty. People who earn any sort of wages make up only a small minority of those who are in poverty.

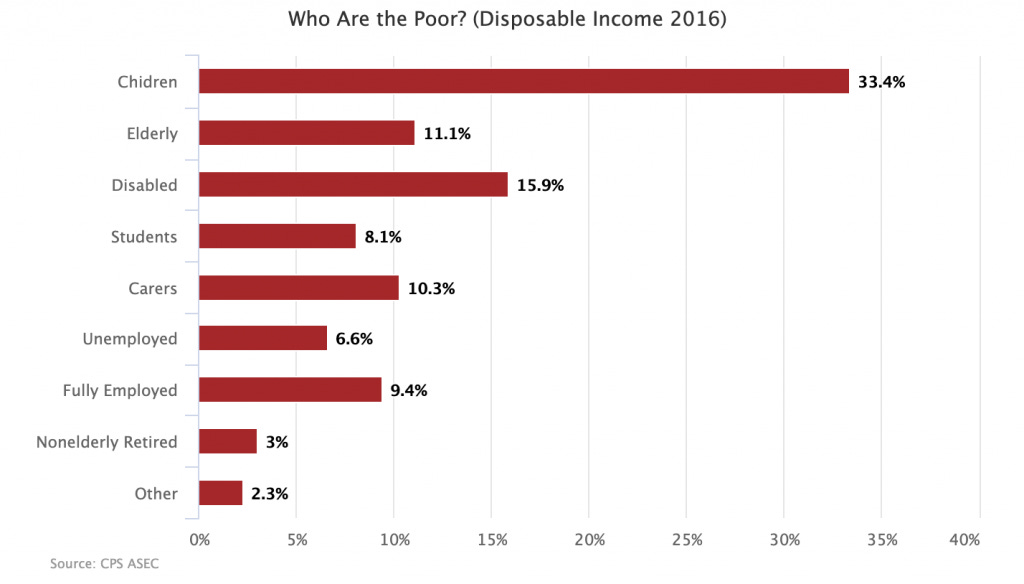

Most people in poverty have no exposure to wages at all. For example, 84% of the Americans in poverty in 2016 were children, elderly, disabled, students, or caregivers. Together, the categories of employed + unemployed only constituted 16% of the poor, meaning issues of low wages could only (directly) affect 16% of those in poverty (note that this doesn’t include part-time work, so the numbers are fuzzy).

To be sure, the condition of low wage work and workers in America needs addressing (though things are improving at the bottom of the wage distribution for the first time in a long time these days!). But Bruenig’s point is that we shouldn’t conflate that issue with “poverty.”

So if we understand poverty as a location that primarily afflicts non-workers, how do we pave over it?

Back to the neuroscience of cessations.

Some preliminary neuroscience on cessations

So, what the heck is going on in the brain of someone who has meditatively switched off their consciousness for some period of time? We can break this down into two lenses: measurements of what’s going on in the brain taken with neuroscience gizmos, and speculation as to what’s going on in the mind.

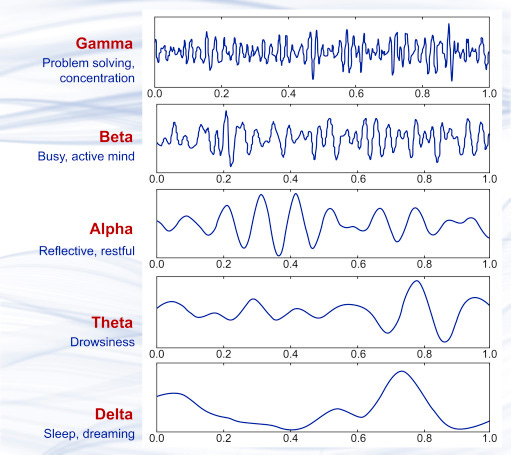

On the brain front, preliminary findings center on the synchrony and desynchronization of brainwave activity. Since brains deal primarily in electrical impulses, you can measure neural activity by measuring electrical activity (with EEG, for example). Brainwaves are just rhythmic and repetitive patterns of this neural activity. Depending on how quick or slow the brainwaves are, they get some different names.

Synchrony refers to how many of the brain’s individual neurons are emitting activity at the same frequency2. The more neurons firing in the 8 - 12 hz range, which is known as the alpha range, the more ‘alpha synchrony' in overall brainwave activity (alpha is the most common frequency that dominates during ordinary consciousness).

The researchers found that about 20 seconds before a cessation, alpha wave synchrony begins decreasing. It bottoms out during the cessation, and after emerging from it, alpha activity begins winding up again.

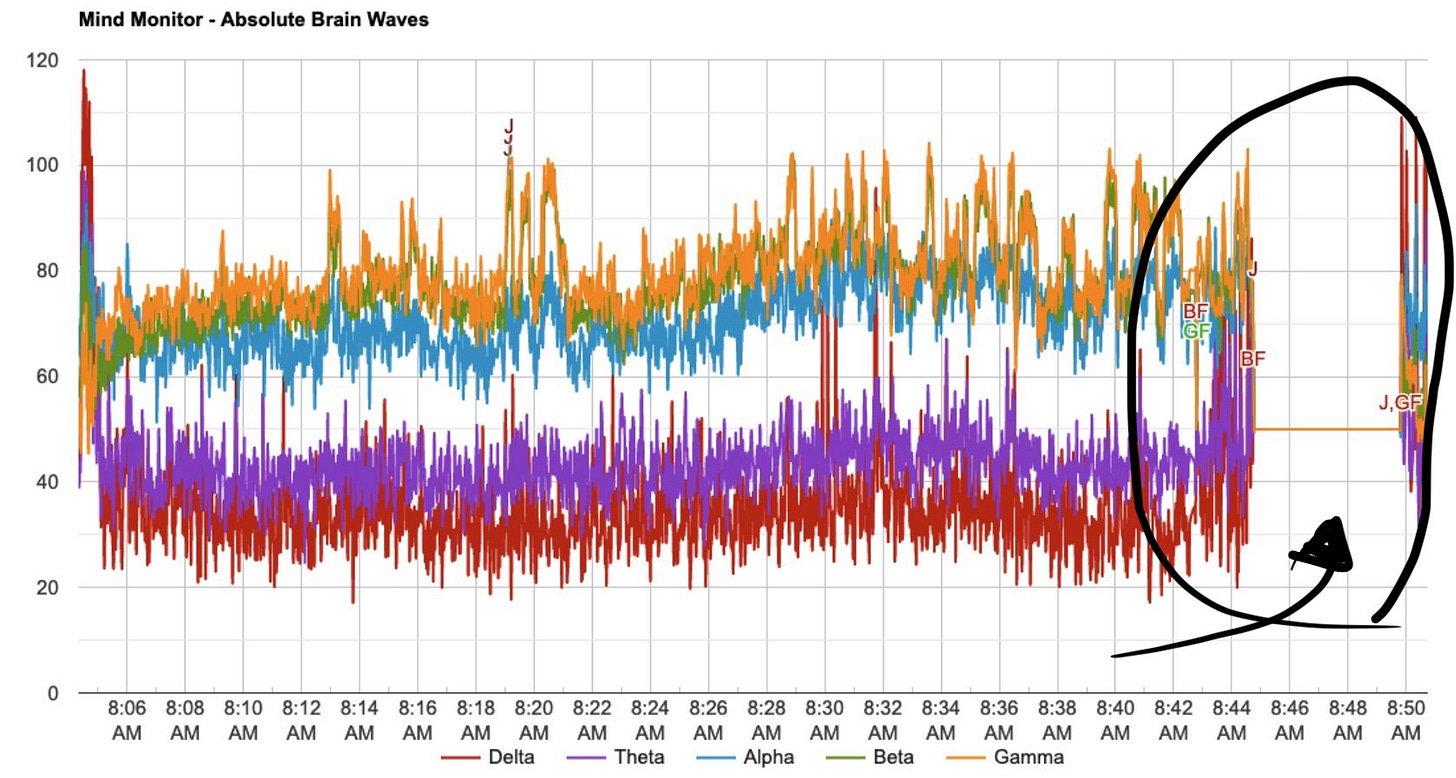

We don’t have the actual data from this yet — that’s forthcoming in a different paper. But we do have something. One of the researchers from the paper (Ruben Laukkonen, who I’ve interviewed on the podcast before) shared an image of brain wave recordings from a Muse headband that records brainwaves (it’s a commercial headband, so very rudimentary, but still) from someone who claimed to be able to enter cessations on demand. In that data, not only alpha, but all brainwaves dropped off during cessation:

Referring to the preliminary data yet to be published, Ruben writes:

Specifically, the breakdown in coherence or synchrony was highest in cessation, followed by the nap, and then the control condition. So, cessation desynchronizes neural activity in the brain, but why, and what does this mean?

Now, we’re moving into the speculative lens on what’s going on in the mind.

Drawing on Integrated Information Theory, one of the defining features of consciousness is that each moment of experiences appears “integrated.” That is, all the innumerable tiny fragments of sensory experience I process in any given moment do not present in my conscious mind as a disintegrated mess of tiny sensory experiences. The mind weaves these altogether into coherent, unified wholes.

What I see as the “table” is actually a collection of tiny little sensory bits (color, shape, etc). Integrating bits of sensory experience into higher-order wholes makes us fantastically more capable of navigating the world in useful ways.

Here’s the key: desynchronizing neural activity (as cessation events appear to do) looks liker the inverse of integrating information.

Ruben explains:

“Desynchronizing neural activity results in a breakdown in information integration: a key mechanism that binds our experience together into a unified whole gets a mortal blow. Similar desynchronization results are found when you take enough propofol or ketamine.

Remember that all our sensory experiences reach the brain at different times and are processed in different areas. If these events are not successfully integrated it is not possible to have a coherent conscious experience. To disintegrate them is to disunify consciousness.”

The philosopher Chris Letheby once described this process to me as “unselfing” with particular attention to how high-dose psychedelics cause the self-model to unbind, explaining the varying senses of ego dissolution.

So the preliminary idea: desynchronizing neural activity may be a signature of unbinding integrated information. As Ruben explained in our conversation, you can unbind conscious experience at increasing levels of depth via meditation, reaching deeper into the underpinnings of the predictive mind.

Cessation, then, might occur when an advanced meditator drives the unbinding process deep enough into the most fundamental integrations of information, such that the entire experience of consciousness simply unravels, leaving no trace.

The authors speculate that cessation may be the dis-integration of the most basic expectation of the predictive mind: the expectation of awareness itself:

To summarize, NS [nirodha samāpatti] may reflect a final release of the expectation to be awake or aware. This could be brought about through (neuro)physiological changes that support a low-arousal, hypometabolic state."

And why is coming out of a cessation refreshing, rather than disorienting, like anesthesia? One option is to speculate that meditators maintain some sort of awareness that is more present while the mind reconstructs itself from the ground up. Put differently, meditators could potentially witness the process of mental reconstruction — taking the unbound pieces of the mind and weaving them all back together again into the integrated holes we ordinarily take for granted — in a way that anesthesia recipients miss.

Coming out of NS may follow a reverse path in which the mind is progressively reconstructed going from simple wake-fulness (e.g., pure awareness) to temporally shallow (e.g., sensory experience) to temporally deep predictive processes (e.g., thinking).”

This would make sense, given that one skill meditators are said to cultivate is precisely this sort of ‘witnessing’ consciousness, an awareness of awareness. The further down the meditative path one gets, the more they’re said to integrate this mode of awareness into their ordinary baseline.

Another somewhat related possibility is that the cessation event functions as a sort of “precision reset” on the priors that constitute the predictive mind. You can think of these priors as assumptions the mind is so sure of that it takes them as given. They thereby elide conscious reflection (saving our attention for other, higher-order reflections). But different assumptions get assigned different “weights,” or confidence levels.

Maybe the cessation resets these confidence levels, which then allows for a different state-space of consciousness to enter into conscious reflection:

If priors undergo a precision-reset—the extent of which may be determined by the depth of the cessation—this would manifest as greater confidence in, and attention to, present moment sensory experience, or phenomenologically a sense of clarity and freshness, as if everything is new or as if “seen for the first time.” Or put simply, cessation would result in an experience of the present moment that is less conditioned by past beliefs.

Putting it all together:

Hence, one possibility is that cessation leads to a kind of inner reset of the precision-weighting landscape at higher-levels in the processing hierarchy, reducing one’s computational trust in priors that encode deep beliefs about (oneself in) the world—which have just been revealed to be highly vulnerable and volatile in light of cessation—and hence increasing the vividness, attention, and confidence, associated with sensorial data. In essence, this represents a shift in the system such that the generative model is driven by bottom-up input more than top-down expectations.

As I wrote about in the last newsletter on a general theory of spirituality, it would be naive to equate “more bottom-up processing” with the totality of spirituality. It’s half the story, at best. Once you’ve fiddled with your ‘generative model’ of the world such that it’s increasingly sensitive to bottom-up input, you don’t necessarily want to live in that state forever (neither do I think you can, the very slope of how cognition works is to reify bottom-up data into hardened, top-down concepts, because that’s an incredibly useful evolutionary trick). Instead, you can ask: how do I want to rebuild my top-down expectations?

Paving over poverty

The economist Thomas Sowell makes the argument somewhere that progressives are too wound up about poverty and inequality because they use statistics that are snapshots of a single moment in time. Sowell argues that it’s better to look at poverty over time, and that when you do so, the disparities shrink. People who are in poverty do not always remain in poverty. People who have low earnings are often young, and make more money as they get older.

This is somewhat true. Many people who are in poverty at some point in their lives tend to exit poverty later on. Snapshots of inequality miss the natural earnings lifecycle of a career.

This is important, but not because it dismisses progressive concerns about poverty or inequality. This just furthers the point that poverty is a location in the system, not a static group of people.

When one person climbs out of poverty, there’s another who fills in. The issue is how deep that place is, how suffused with depravity and despair those depths are, and how those experiences leave indelible marks on the lives — and minds — of those who pass through.

The issue is that things could simply be otherwise. We could devise a generous social safety net that fills in the depths, such that being in the lower end of the income distribution is not a miserable, damning existence amidst a country so flush with resources. We could provide an unconditional child allowance, as many other rich countries do, drastically reducing child poverty. And since child poverty is one of the biggest categories of those in poverty overall, this would also make big progress on aggregate poverty itself.

Instead, we remain caught on assigning personality traits to a demographic that doesn’t actually exist, at least not how our ordinary language invites us to imagine. Joe Manchin single-handedly drove 2.7 million children back into poverty, a corrosive location that we could simply decide will no longer exist.

Cessation of poverty

Cessations occur by progressively desynchronizing neural activity until consciousness unravels entirely, without a trace. When Desmond advocates for poverty abolitionism, I imagine an economic variety of cessation.

Via careful policy interventions, we could desynchronize all the various life-paths and economic conditions and individual behaviors from the location of poverty, until there is simply no path left that leads from being an American citizen to living in poverty3.

Just like sufficient desynchronization of neural activity eventually reaches a point where consciousness just disappears, sufficient desynchronization of any form of life with incomes below the poverty threshold would eventually lead to the entire location of poverty falling off the map of the U.S. To deepen the cessation, we could simply raise the poverty line, and do it over again.

Tying together things like cessation and poverty is one of my particularly weird interests — but through this newsletter and the podcast, I’ve learned there are plenty of others out there. This collective readership is far more inventive than myself alone, so why not leverage that?

I’m going to start a Substack chat thread for any thoughts, responses, or ideas of their own folks might have to drawing together disparate things like cessation and poverty, or contemplative science and economics. This can also help me decipher if these Substack features are worthwhile.

Here is a link to the chat, go nuts. Stranger the better.

Until next time,

Oshan

This is a new one for me, very uncertain. If you see any holes to poke, please do (I see a few, but none that really take down the sentiment that conflating the issue of low wages with poverty seems to miss most of who’s really in poverty).

This is my layman’s interpretation, which is very likely imperfect.

While America’s conditions of poverty are relatively worse compared to similarly rich nations, I’m aware of my domestic bias here. For global poverty, I’ll just defer to Give Directly.

This was really great to read. Thanks for writing and researching it. One thought I had relating to poverty as a location is from the book Sex and world Peace by Valerie Hudson and others. The book mentions that being born a woman and having given birth to a child increases the statistics of being poor later in life because that path leads you through a location (childcare) where you aren’t building your own career for a long time and where you have little to rely on when “retirement” comes. I’m liking this “location” way of thinking about poverty. “Paving over” feels like an aggressive, urban way to talk about metaphorical locations that while miserable may also be hold a few, rich important experiences to those who experience those “locations”.

Cessation also makes sense to me as I certainly have had to re-build my top-down understanding of the world from evidence contrary to it. You gave me some good language for that.

Very cool and very unexpected cross-connection (those are the best kinds)!

I will be thinking about this one as I keep going with my day.